MICHELLE: You didn’t think we were going to let a CLAMP MMF go by without devoting a special Let’s Get Visual column to it, did you? (Insert a Hokuto Sumeragi “ho ho ho” laugh here.) It’s an absolute must for a group like CLAMP, whose output is so diverse, not merely in the realms of story and demographic, but also artistically speaking. In fact, I had a pretty tough time choosing which images to talk about today. How about you, MJ?

MJ: Yes, there’s so much to choose from! Though CLAMP is nearly always clearly distinguishable as CLAMP, they manage to do that while also significantly varying their style from series to series, especially when they’re writing for different demographics.

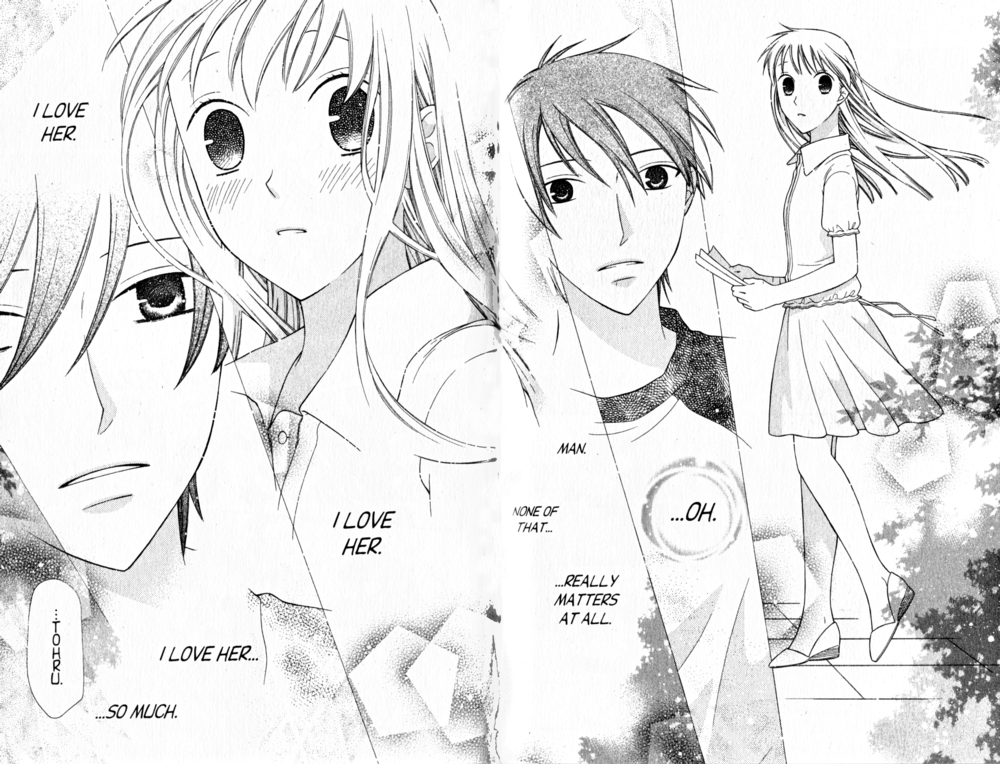

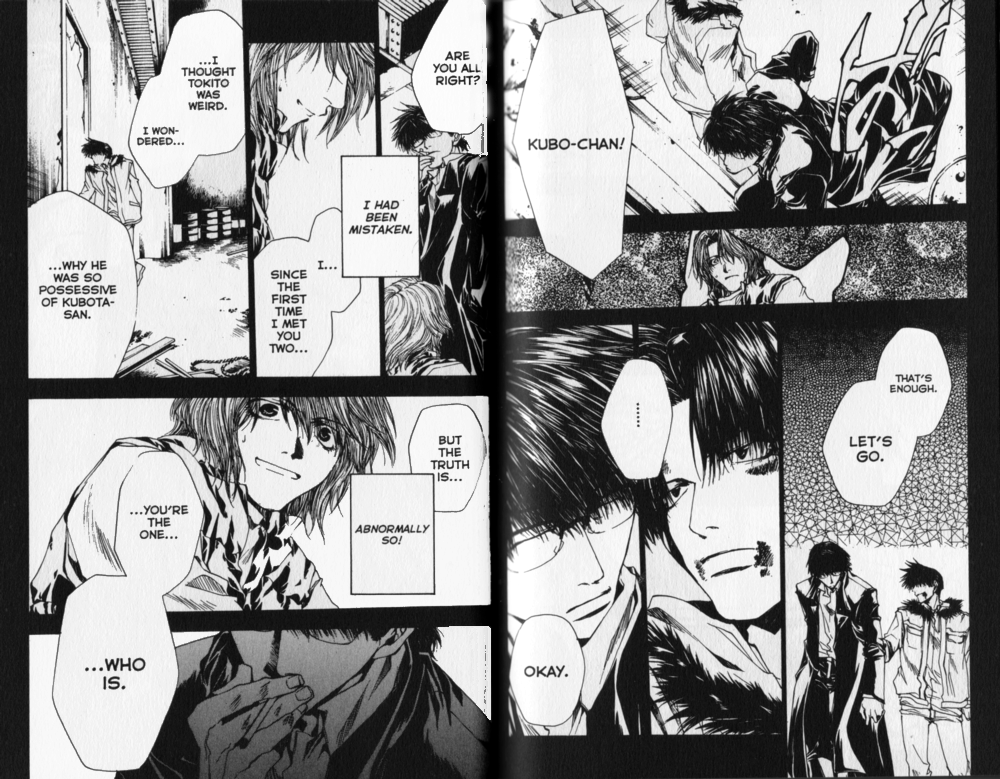

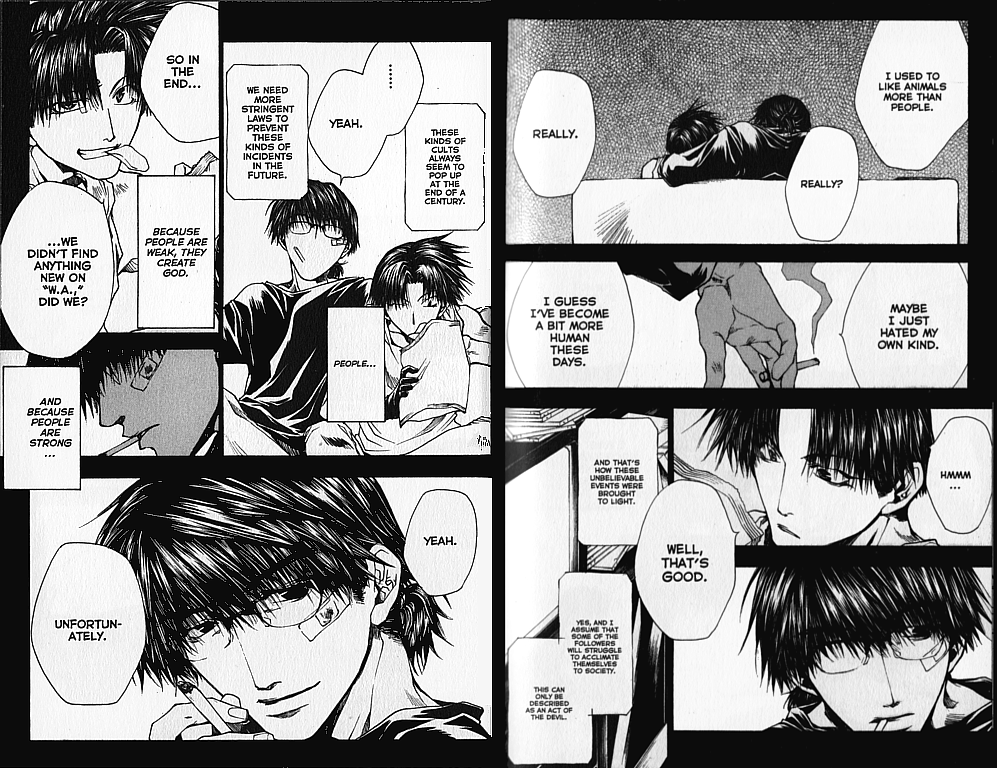

MICHELLE: I wish I had the artistic vocabulary to really thoroughly describe these subtle variations, but I’m afraid I don’t. Still, this diversity inspired MJ and I to compare two CLAMP series with different art, but similar stories. Legal Drug has been described as a prototype for xxxHOLiC, as it features a hyper protagonist (Kazahaya) and his more stoic companion (Rikuo) who are asked to perform various odd, supernatural-related jobs by the precognitive manager of a store (Kakei). Kazahaya is quick to proclaim that they’re not friends, but is forced to begrudgingly thank Rikuo for several timely rescues. This is a setup very similar to the initial relationship between Watanuki and Doumeki in xxxHOLiC.

MJ: Personally, I think you could even make an argument for Kakei’s companion Saiga as a weird prototype for Mokona.

MICHELLE: Yeah, I guess he does spend the majority of his time either sleeping or pulling off surprising domestic tasks.

Anyway, how about you start us off with the pages you’ve chosen?

MJ: Sure! I’ve picked out a couple of different scenes from volume twelve, and the reason I chose that volume is that it’s really where Watanuki’s reality starts to fall apart. At first, he’s simply having a series of strange dreams, but by the end of the volume, dreams and reality are melding into each other, one after the other, to the point where it’s impossible for him to tell the difference between them.

(Click on images to enlarge.)

xxxHOLiC, Vol. 12, Pages 30-32 (Del Rey)

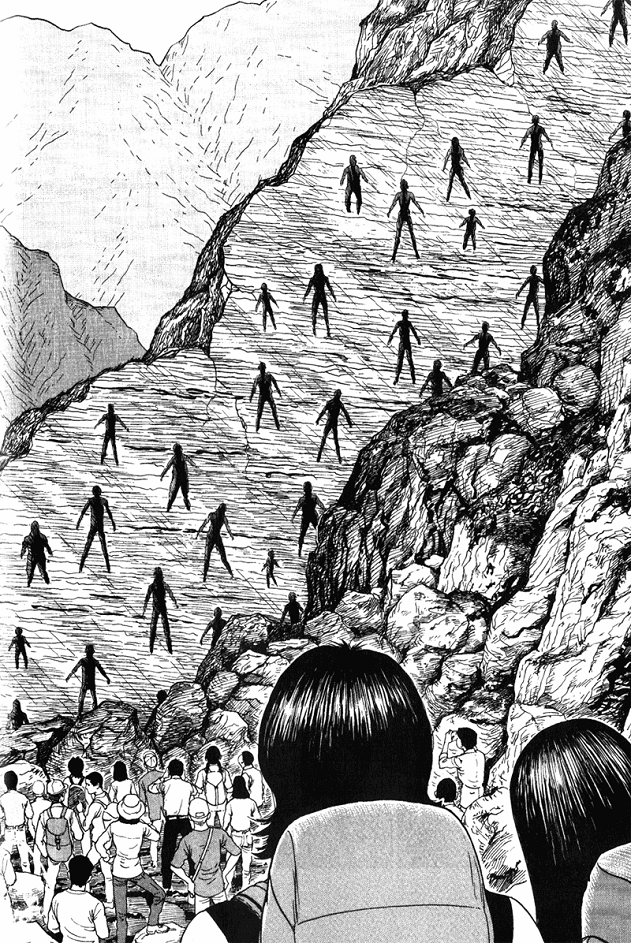

The first scene I’ve chosen comes in early in the volume, and it’s very obviously a dream world. The ever-present blossoms in the wind, Yuuko’s train of butterflies, the wind in the air, and even just the sense of space feels entirely like a dream—like something clearly outside our waking reality. It’s beautiful, but it’s expected, and even when there’s a sense of eeriness, it feels friendly and familiar.

xxxHOLiC, Vol. 12, Pages 138-141 (Del Rey)

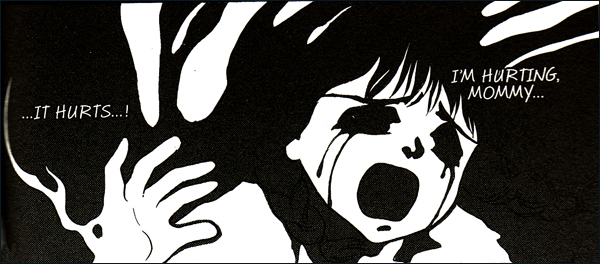

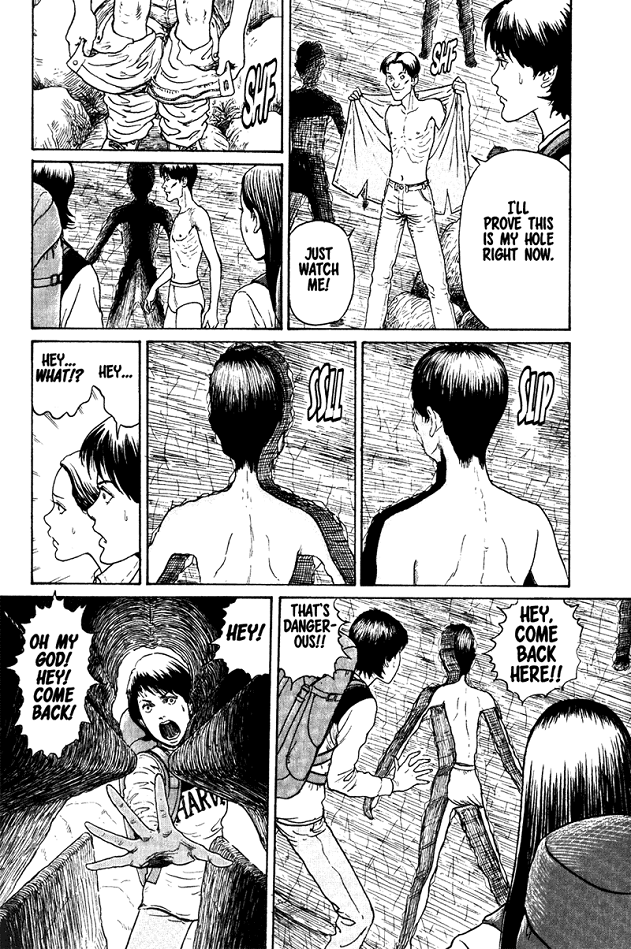

The second scene, on the other hand, comes in much later, when Watanuki is being shuttled from dream to dream to dream, never knowing if he might finally be awake. The scene starts out simply with the kind of lunch picnic he might have with Himawari any day of the week. The backgrounds are sparse and the panels sort of matter-of-fact. The only hint at first that something might be off, is the hole Watanuki notices in the wall behind Himawari. And even though the scene becomes comedic, with the scaly hand popping out of the hole to steal Watanuki’s sherbet, it feels very sinister to me—not just because Himawari never notices what’s happening, but because it’s intruding on what feels to Watanuki like normal life, letting him know that he’s somehow *still* not awake. Unlike the earlier dream scene, which feels so perfectly dreamlike, this one reads as something more like madness, which is much scarier to me as a reader.

MICHELLE: My first reaction when I saw the scaly hand stealing the sherbet was to deem it “cute” but that’s because it’s been so long since I read xxxHOLiC that I had utterly forgotten the context of this scene. Now that you’ve informed me, I read it as sinister. It’s definitely something that could look like “Watanuki’s everyday life” to the casual reader as much as to Watanuki himself, at first.

MJ: I probably am letting the context influence me, which maybe makes this not the greatest example for a Let’s Get Visual column! But I do think it’s interesting how differently CLAMP treats these two scenes, when they’re both representations of Watanuki’s dream world.

MICHELLE: Oh, I think they’re fine examples! What you’re basically showing here is that in xxxHOLiC, or at least in these scenes, CLAMP draws the supernatural in a way that blends in with the everyday world. It’s a very simple approach, free of some of the bells and whistles that my images from Legal Drug possess.

MJ: Well, let’s take a look at those, then!

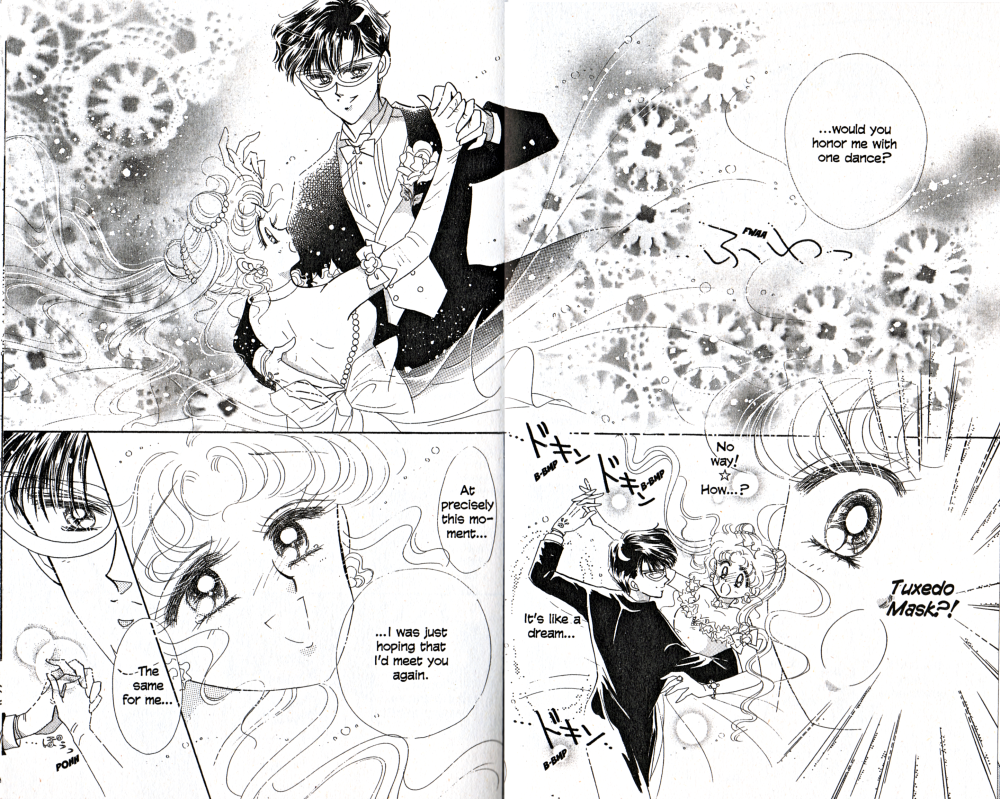

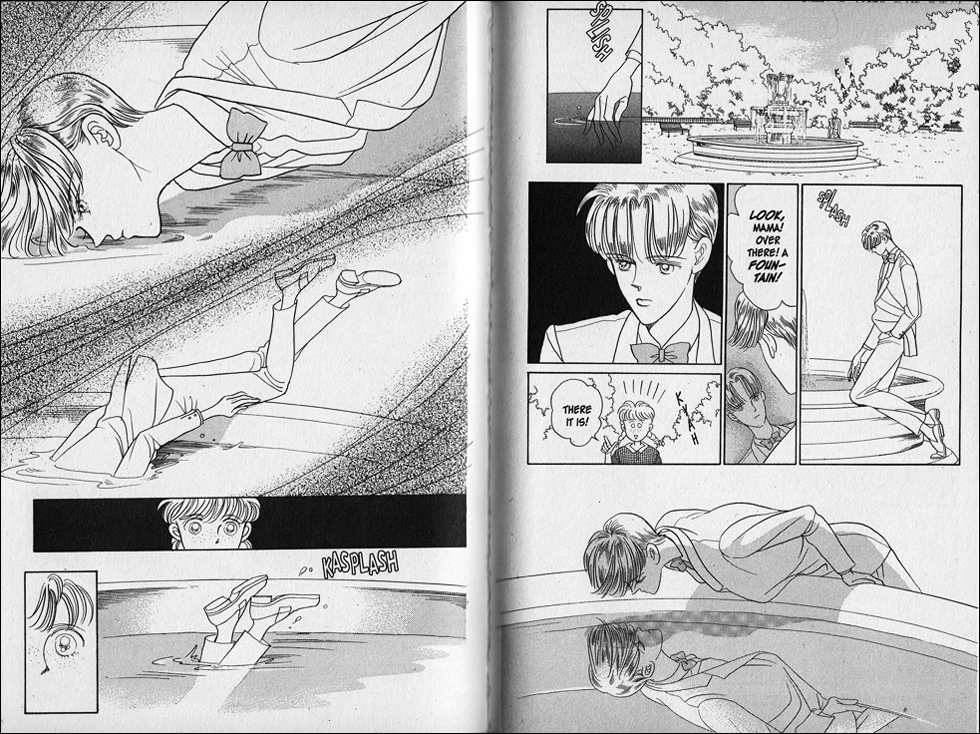

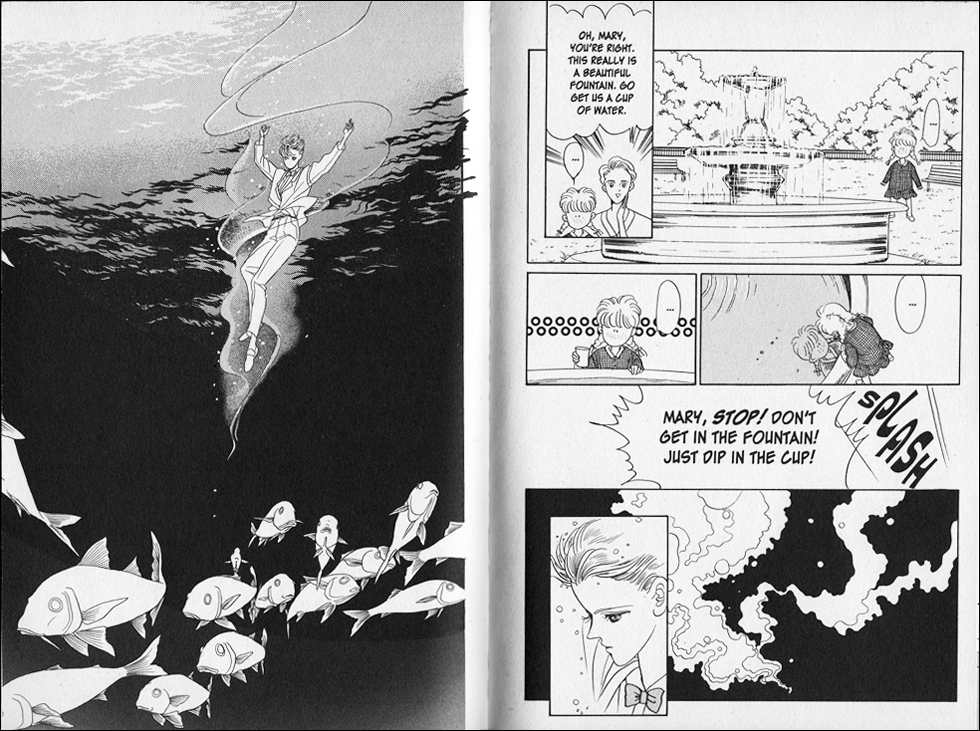

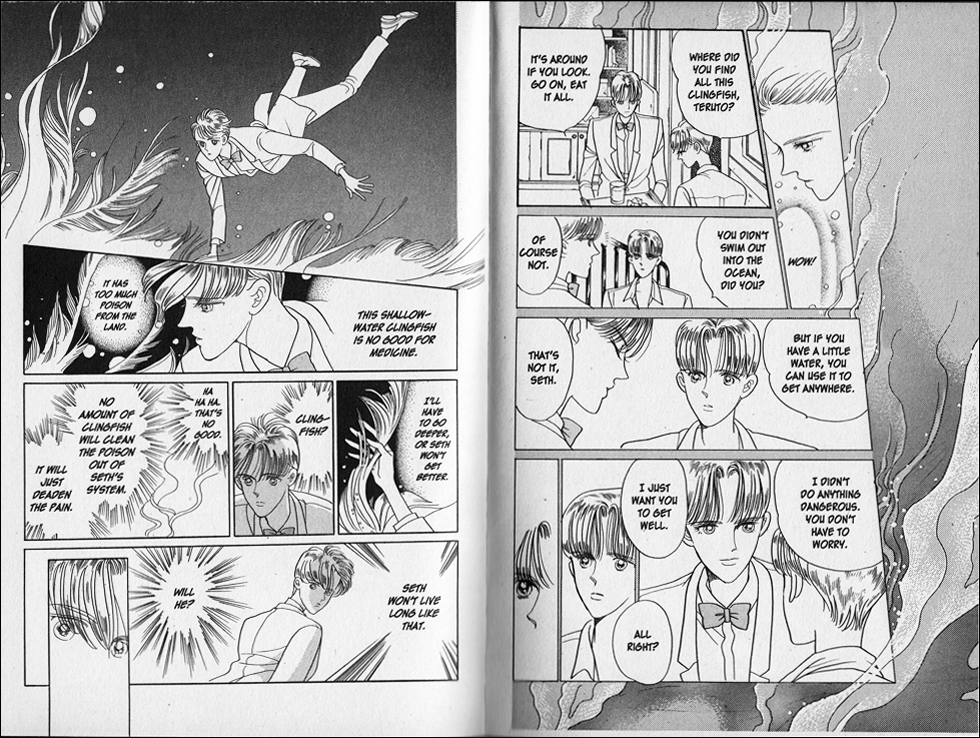

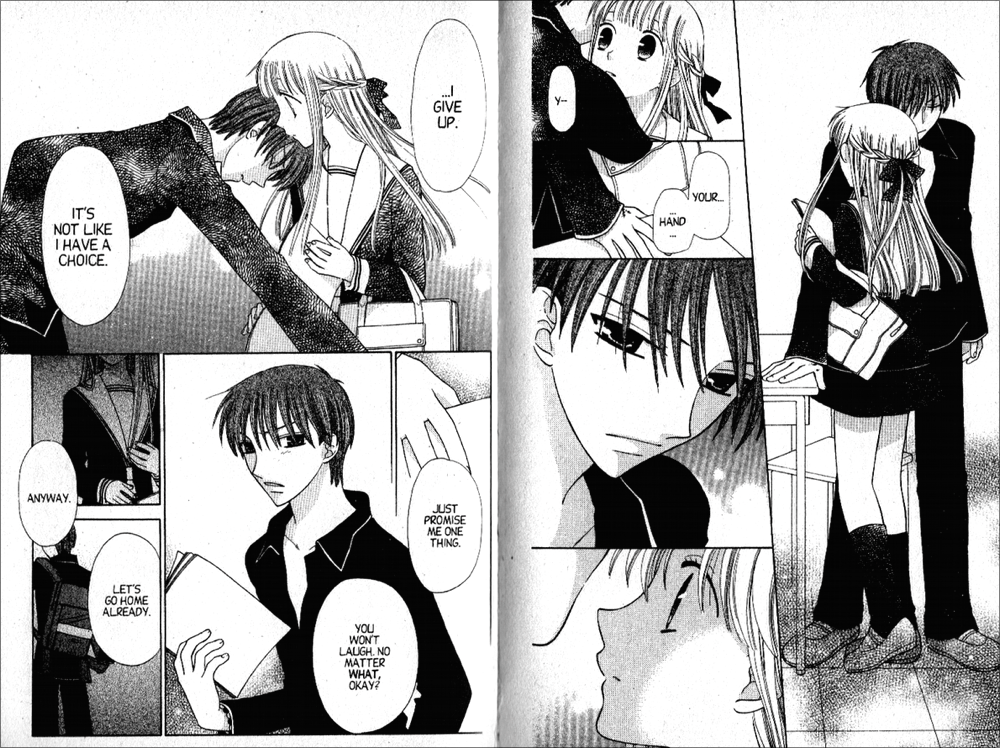

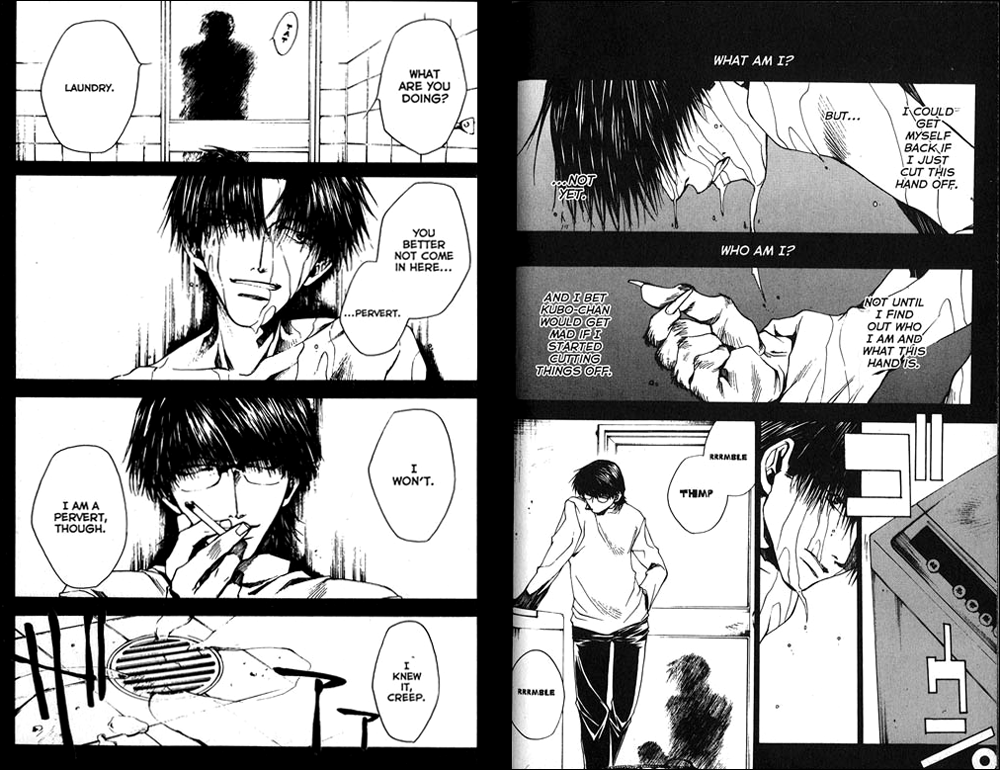

Legal Drug, Vol. 2, Pages 40-43 (TOKYOPOP)

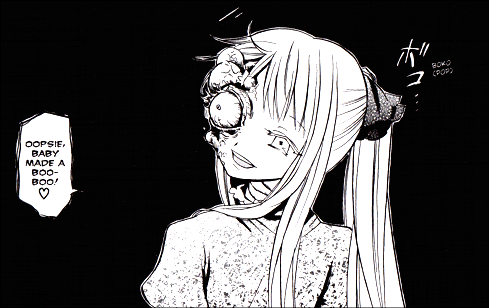

MICHELLE: These pages are from a scene in the second volume of Legal Drug. Kazahaya and Rikuo have just rescued a magical kitty, and in gratitude, the kitty has led them to the park where its powers are strongest and transformed into the images of the person each boy wants to see most.

What struck me strongly here is the way the kitty begins to unravel. Seriously, the fact that it’s just one little toe of his little paw really gets to me somehow. Somewhat like xxxHOLiC, there’s that feeling of “You thought things were normal, but really they are not.” As the transformation is underway, we get several reaction shots from the boys (with a bevy of speedlines), resulting in a page layout far busier than xxxHOLiC. The two-page spread is quintessential CLAMP: two slim and lovely ladies with long flowy hair speckled with white ink. The tight panels of the boys’ eyes include more speedlines to help convey their shock.

Honestly, besides the slightly more ornate style here, it’s the speedlines that really convey the biggest tonal difference between these series to me. It’s presumptuous to declare that CLAMP “matured” between the two series, but it really does feel as though they realized they no longer needed to rely on such tricks to convey the protagonist’s feelings. Less is more!

MJ: Well, I think it’s probably worth bringing up the fact that Legal Drug ran in a shoujo magazine, where those kinds of flourishes might have been expected, unlike xxxHolic, which had to fit in to the style of a seinen magazine. I mean, CLAMP is always CLAMP, but there’s always a clear sense of what demographic they’re drawing for—even in two series as similar as these.

MICHELLE: That’s a good point. I certainly don’t mean to disparage the style of Legal Drug or insinuate that it’s inferior, but in terms of personal preference, I simply like the cleaner, restrained style of xxxHOLiC more. I mean, just check out how the panel shapes themselves are different. It’s really neat to compare them!

MJ: Oh, I completely agree! And though I also have a preference for the artwork in xxxHolic, I do appreciate the shoujo flourishes for their classic flair. More and more, I find the differences fascinating, and I was really surprised, actually, at how easy it was to tell which demographic CLAMP was writing for simply by looking at the artwork of their series in preparation for this Feast. I don’t think I expected it to be so obvious.

MICHELLE: I wouldn’t have, either. But going forward I’ll be making a special point to notice how they adapt their style to the magazine!

Recent Comments