MICHELLE: Hey, MJ, did you know there was a Wild Adapter MMF going on?

MJ: I’ve heard rumors to that effect. Terrific series, Wild Adapter. Whoever is hosting it must have great taste!

MICHELLE: I’m relieved you think so, because in honor of the Feast, we’re devoting this month’s Let’s Get Visual column to that series!

MJ: We are? Oh! Yes, we are!

MICHELLE: One of the hosts has already done an admirable job scanning some of the many significant images from the series (at great personal cost) but that won’t stop us from talking about a few more.

In Wild Adapter, creator Kazuya Minekura tells her story through the eyes of observers. Sometimes these figures are opposed to our main protagonists—Makoto Kubota and Minoru Tokito—in some way, such as the detective in volume four or the new youth gang leader in volume six, and sometimes they are with them, either in a personal way (their young neighbor Shouta in volume five) or a more business-like fashion (Takizawa the journalist in volume three). In every case, though, we rely on their interactions with Kubota and Tokito to learn more about said fellows, since we are denied access to their thoughts.

As I reread the series, I noticed that Minekura also uses her art to support this narrative choice, and that she, in particular, uses a similar device several times where Kubota is concerned. (Click on images to enlarge.)

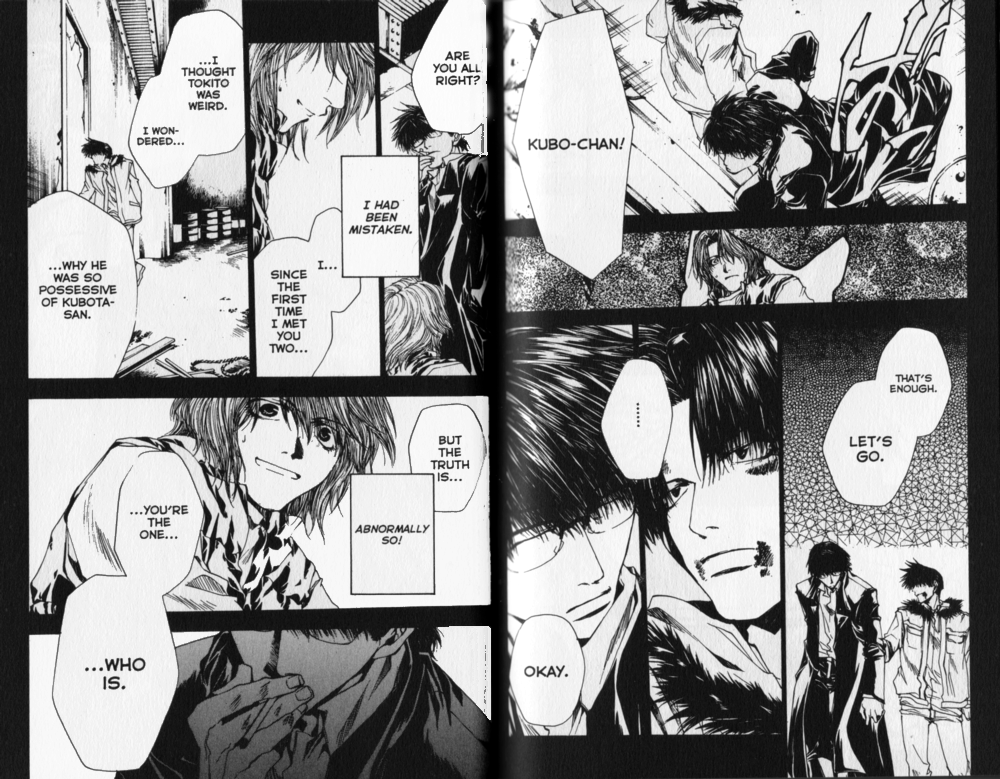

Volume 2, Chapter 11 (TOKYOPOP)

Here, Tokito stops Kubota, who has violently come to his rescue. Kubota instantly sheds any vestige of excitement, and throughout this two-page spread, his eyes, like his thoughts, feelings, and motivations, remain shielded. He’s distant and aloof. Yet when Saori suddenly realizes that Kubota is the one who’s possessive of Tokito, he offers her a small smile. She finds the experience scary, and I agree that it could be construed as an ominous expression, but it’s also a stunning moment of access to what Kubota feels.

MJ: I agree that it’s a stunning image, and while I can appreciate Saori’s response, like you, I’m mostly fascinated. As you say, Kubota is a character who deliberately shuts himself off from other people, and now, as we’re granted this tiny moment of access, it becomes really clear why. In these rare moments, with just a small smile and a real look into the eyes, he’s suddenly wide open to us, and the guy that we see in there is nothing like the person he displays the rest of the time. And that’s a guy he really doesn’t want people to know. Maybe he thinks that guy is scary, I don’t know. But it’s clear that when he does grant access, he’s pretty much an open book—probably more so than characters who are generally open to begin with. Does any of that make sense?

MICHELLE: It does, and you’ve provided me with an excellent introduction for my next example!

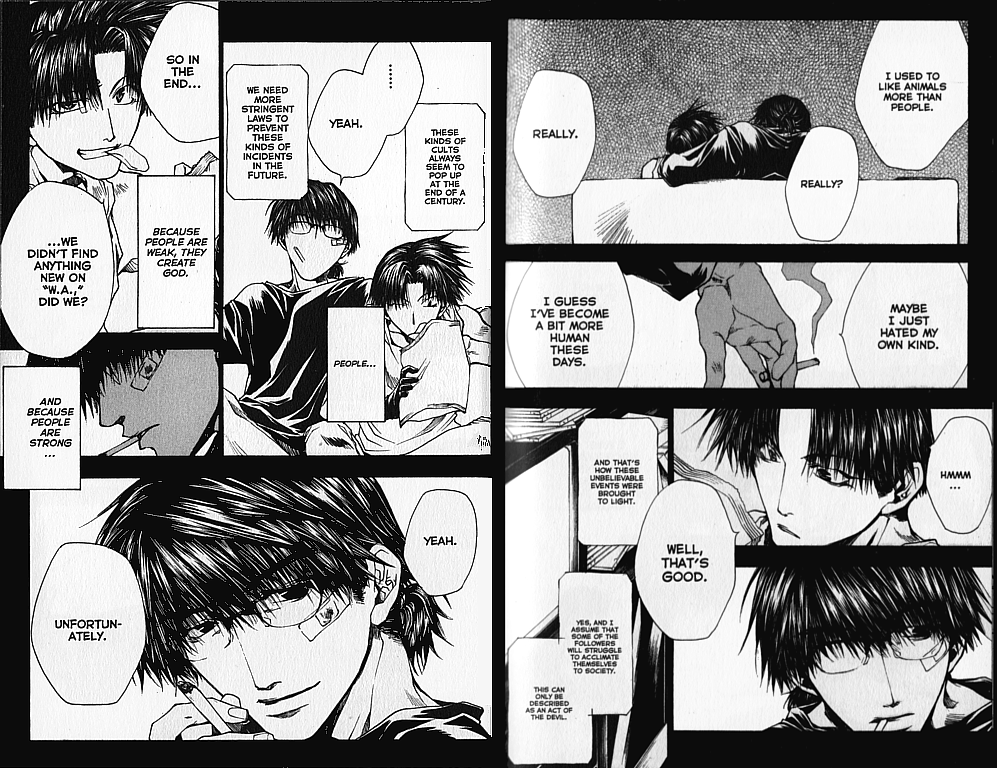

Volume 3, Chapter 18 (TOKYOPOP)

This scene takes place near the end of volume three, during which Kubota and Tokito have infiltrated a cult that they erroneously believe is connected to Wild Adapter. Here, the guys are looking very casual and cozy, and while Kubota admits to Tokito that he has become more human, he does it while facing away from the audience. We see the back of his head and a hand holding a cigarette as he speaks. This is a moment reserved for he and Tokito alone.

Kubota doesn’t say it outright, but it’s clear that it’s Tokito making him feel this way. And when Tokito goes on to lament their progress in their investigation, the warm and open-eyed smile of Kubota’s at the bottom of page two makes it clear he hasn’t yet changed mental gears. He’s still thinking about Tokito.

MJ: To me, these soft, openly caring eyes are just as much of a shock as the more terrifying look we see in your first example. It’s clear that both of these looks are genuinely Kubota, but you get the feeling that Tokito is the first thing that’s ever inspired the feelings behind this look.

I have to really admire Minekura’s skill with expression here, too. Though some aspects of her artwork are very detailed, she actually doesn’t include a lot of detail when it comes to eyes. Yet what she’s able to do with just the barest nuance is, frankly, incredible.

MICHELLE: But wait, there’s more! Minekura uses this technique again in volume four, with very different results!

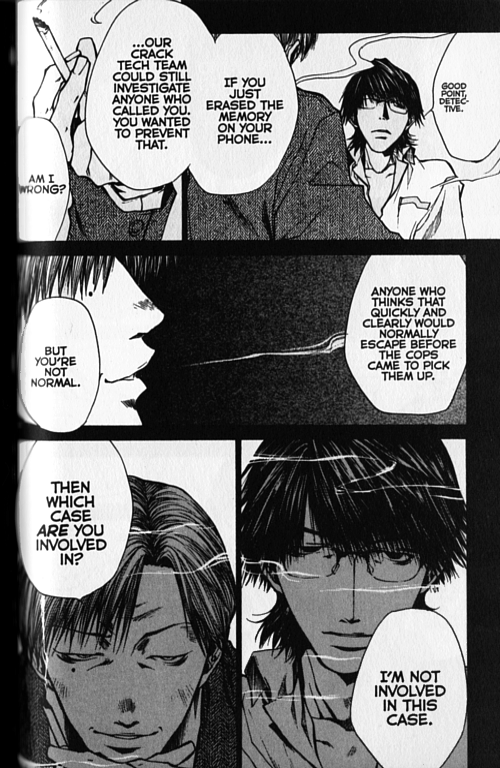

Volume 4, Chapter 22 (TOKYOPOP)

Here, we see Kubota being interrogated by Hasebe for a murder that was committed in a hotel. Kubota’s not giving up any information, so it makes perfect sense that he would be evasive, as indicated by the closed eyes on the first page. Hasebe continues to push, however, and Kubota finally gives up pretense and opens his eyes, allowing us access once more. Only this time, we’re not seeing a warm and friendly Kubota; we’re seeing a coldly resolute one. The grey screentone over his face emphasizes that this is just a partial disclosure—he’s revealing the extent of his determination, but anything else is still off-limits.

MJ: It’s the narrowness of his gaze that really achieves this effect, but again, it’s done with most subtle detail. And you’re right, he’s giving the detective just exactly as much as he wants to give him, no more, no less. It really gives you a strong sense of how carefully he controls everything about himself, and just how rare the two previous examples really are.

MICHELLE: Yes, you’re quite right! The amount of openness Kubota will permit with other people is infinitesimal compared to what Tokito is allowed to see.

Well, that’s it for me and Kubota’s eyes. What images did you want to talk about?

MJ: I’d like to talk about a scene from the end of volume two. It’s one I’ve discussed a couple of times before, both in my initial review of the series and in my infamous post on “intimacy porn.” It’s one of my favorite scenes in the series, and I’ve already explained quite a bit about why.

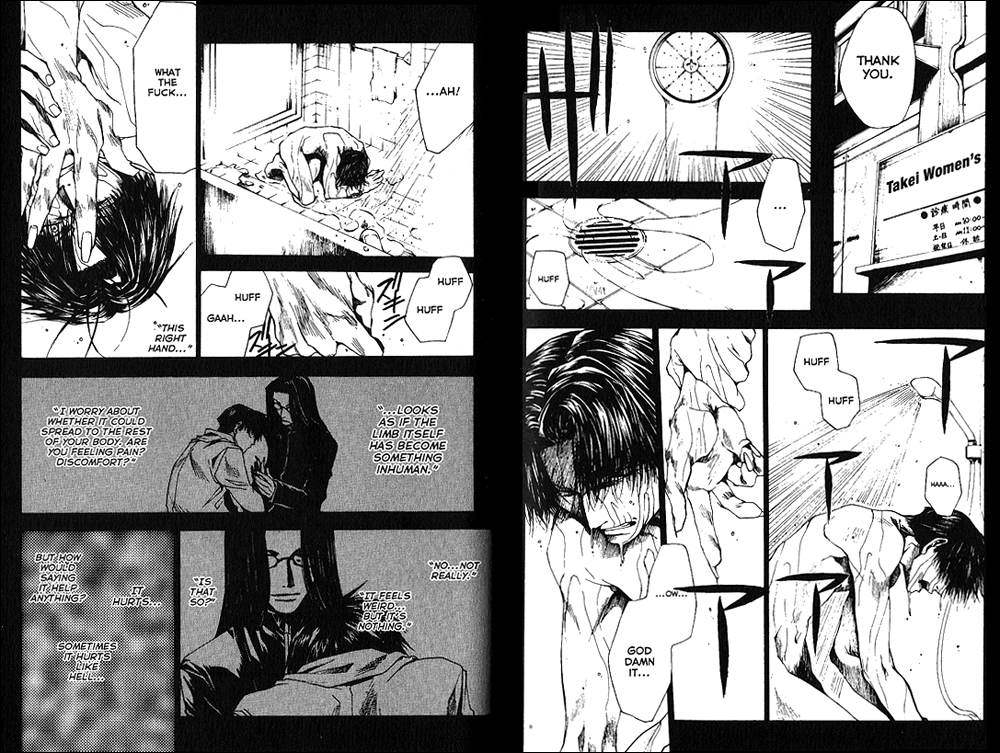

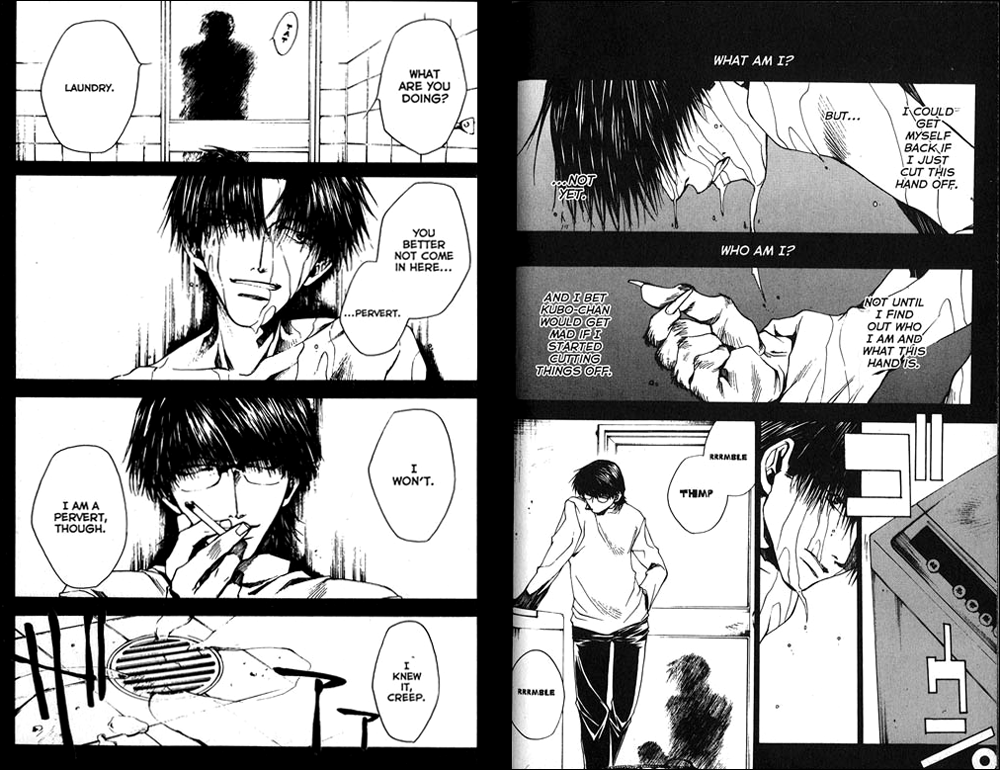

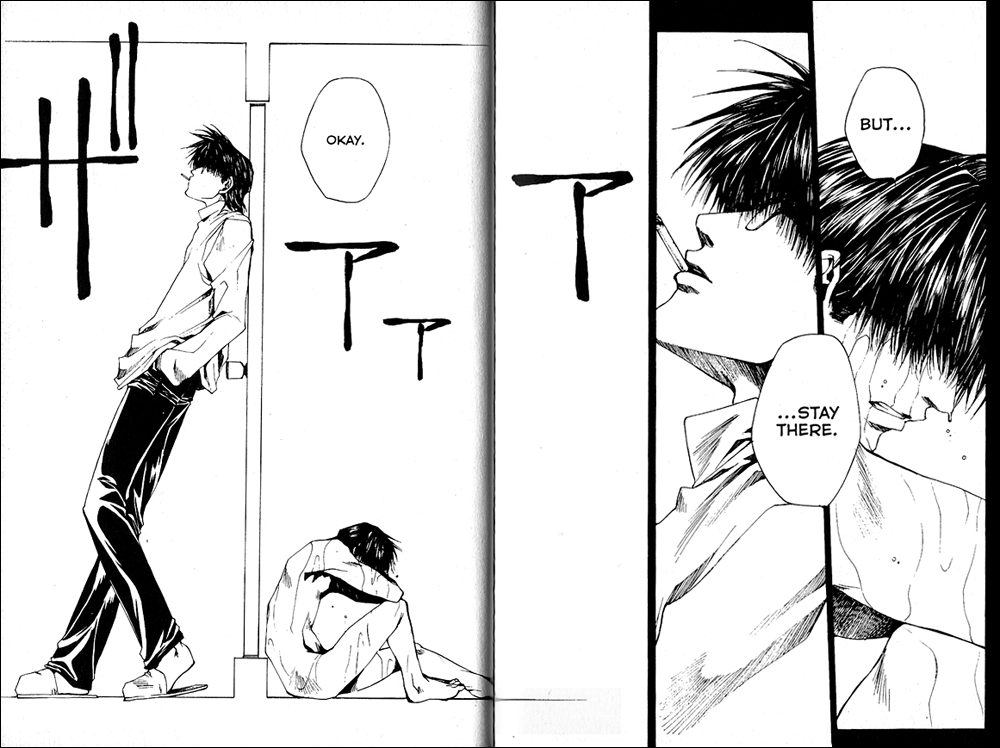

Volume 2, Chapter 12 (TOKYOPOP)

As you can see, Tokito has hidden himself away in the shower to deal with pain in his claw hand, and as he wrestles with both the physical pain and emotional turmoil the hand causes him, he realizes that Kubota is on the other side of the shower door, doing laundry.

When I’ve talked about this scene before, my focus has always been on the incredible intimacy of it, and how beautifully Minekura creates this intimacy while putting a physical barrier between them. What I’ve never discussed before, however, is the detail that, in my view, is almost solely responsible for bringing us into the scene as readers, and that would be the sound effects.

I have no idea what the sound effects really say. I don’t read Japanese, and I haven’t asked anyone to interpret them for me, but really, I don’t have to. It’s actually the visual effect of the Japanese sound effects that makes them so effective.

We feel it from the beginning, with just Tokito—the soft sounds of the shower accompanying his thoughts. Then the rumble of the washing machine joins in as Kubota enters the scene. By the end, we’re surrounded by it all, the soft shower and the muffled rumbles of the machine, creating a shell of sound around the characters, isolating them from the rest of the world, but including us as intimate onlookers.

I’m always impressed by writers and artists who can create a real sense of place on the page, and Minekura has done this by surrounding us in these familiar sounds. We can imagine ourselves in the room—feel the rumble of the washing machine under our feet and the thick humidity of the steam as it wafts out around the edges of the shower door. It’s so beautifully done.

MICHELLE: Oh, I love the image of a shell of sound. I like, too, how the initial thump of the washing machine literally intrudes onto Tokito’s thoughts in the way that the sound effect bleeds over the edge of its panel and onto the next, where Tokito, with water streaming down his face, has now been momentarily distracted.

MJ: Yes, I love that frame you’re talking about, where the sounds of the washing machine suddenly intrude into Tokito’s thoughts. It’s as though the washing machine has spoken up to say, “We can hear what you’re thinking in there, and yes, he would be angry if you cut off your hand.”

MICHELLE: Do you actually want me to tell you what the sound effects say? Or is it better not to know?

MJ: Sure, tell me!

MICHELLE: The first one you see, and the one that appears most often and prominently, is “zaa,” which is frequently used alongside rain or falling water. It’s the “a” sound that travels down that first page and drifts across the final two-page spread. On the second page, when Tokito clenches his hand in pain, the sound effects say “zukin zukin,” or “throb throb.”

I was unfamiliar with the “goun” sound accompanying the first image of the washing machine, so consulted Google and found a site that helpfully describes “goun” as “the sound of a washing machine.”

MJ: Ah, helpful indeed.

MICHELLE: One of my motivations for teaching myself kana in the first place was to be able to decipher untranslated sound effects. It slows me down, reading each and every one, but it does add something to the atmosphere, I find.

Another thing I notice in this example is how Minekura treats the “zaa” sound effect, allowing it to trickle down the page along with the water in the first instance, and in the last, depicting it wafting laterally past Kubota, almost like escaping steam.

MJ: What’s really amazing to me, is how successfully this effect is achieved even without understanding the kana. The visual representation of the sound is so powerful all on its own.

MICHELLE: Definitely. Even if the sound effects weren’t there at all, one would still imagine the sound of running water. Their presence emphasizes the sound and its insular quality, though. I’m reminded of an earlier column, where we talked about the sound effects in Banana Fish. There, an image of a passing train automatically conjured the associated sounds, but the sound effects, through their domination of the page, took it to the next level by mirroring how the sound dominated the moment for the characters.

MJ: Here, the sound sort of cradles the moment, creating a sense of comfort and familiarity around something extremely vulnerable.

MICHELLE: Ooh, good verb. In both cases, the sound effects define the sound in some way, rather than simply reiterating that it’s there.

MJ: When I first started reading manga, I found sound effects distracting. I was so new to comics, I had a lot of trouble digesting all the visual information on the page, and sound effects just made that more difficult. Over time, however, I’ve come to appreciate just how much they contribute to the atmosphere of a scene, and how powerful they can be in the right hands.

MICHELLE: It’s like this whole other tool in the mangaka’s kit, and one that we don’t automatically think about.

MJ: Well said!

MICHELLE: Which brings us back around to the inescapable truth that Kazuya Minekura is brilliant and everyone should read Wild Adapter.

MJ: Yes, they should!

For more reviews, roundtables, and essays on Wild Adapter, check out the complete MMF archive.

Recent Comments