By Takehiko Inoue | Published by VIZ Media (first VIZBIG edition)

One of my goals for this Manga Moveable Feast was to finally read some of Vagabond. I’ve been collecting the VIZBIG editions since they started coming out, which means there were ten of these on my shelf (with their spines forming a group portrait) unread. Now that I finally have read some of Vagabond, I’ve found it so different from the Inoue I’m familiar with—and yet containing some of the same themes—that I’m rather at a loss for words.

One of my goals for this Manga Moveable Feast was to finally read some of Vagabond. I’ve been collecting the VIZBIG editions since they started coming out, which means there were ten of these on my shelf (with their spines forming a group portrait) unread. Now that I finally have read some of Vagabond, I’ve found it so different from the Inoue I’m familiar with—and yet containing some of the same themes—that I’m rather at a loss for words.

Shinmen Takezo is the son of a legendary swordsman, though we don’t really find that out until volume three. Since the age of thirteen, when he killed a man who came to Miyamoto village looking to challenge its strongest occupant, he’s been ostracized by all save a couple of childhood friends and he’s recently been off to battle with one of them, Hon’iden Matahachi. They both survive a bloody battle, but Matahachi takes up with a thieving widow, leaving Takezo to return to Miyamoto with tidings of Matahachi’s survival.

To make a long story very short: Takezo meets with an unfriendly welcome and is manipulated by a clever monk named Takuan into reevaluating his life. Four years later, now going by the name Miyamoto Musashi, he shows up in Kyoto looking to challenge the head of the Yoshioka sword school, and though he defeats many of their members, he learns there are still those stronger than him. A drunken Matahachi accidentally sets the blaze that allows Musashi to escape, and the VIZBIG ends with him realizing that the old friend he left for dead might actually have survived.

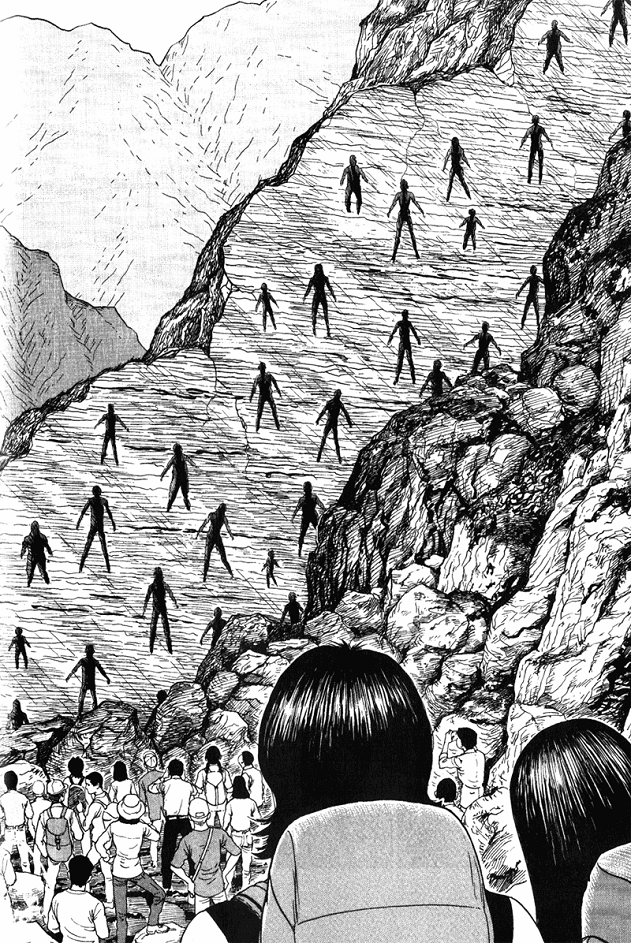

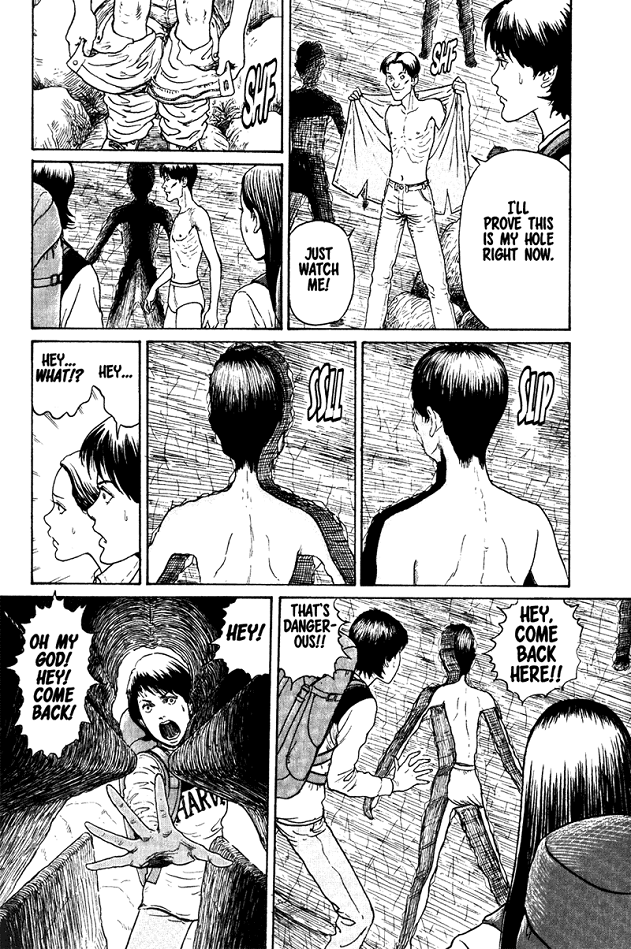

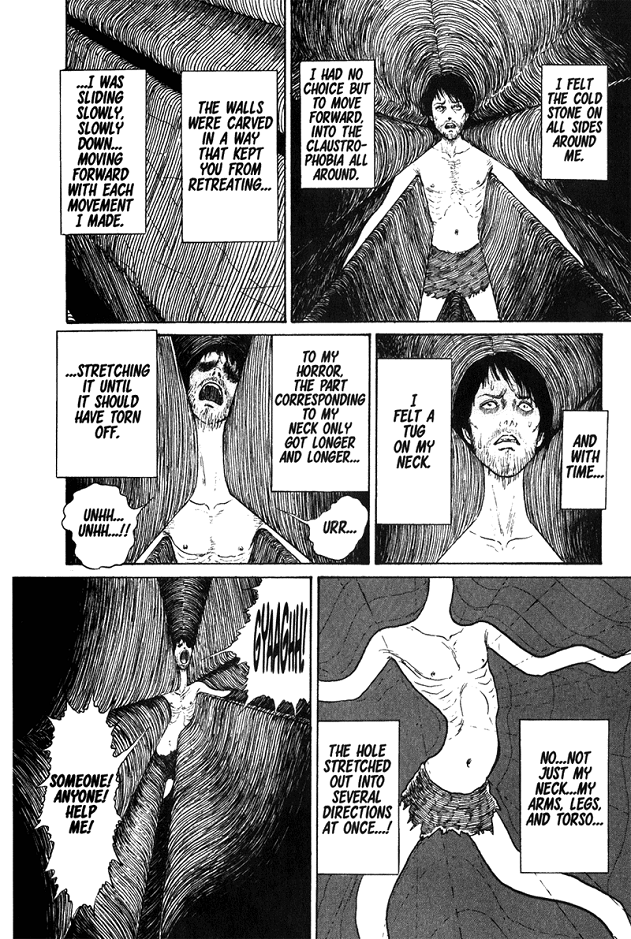

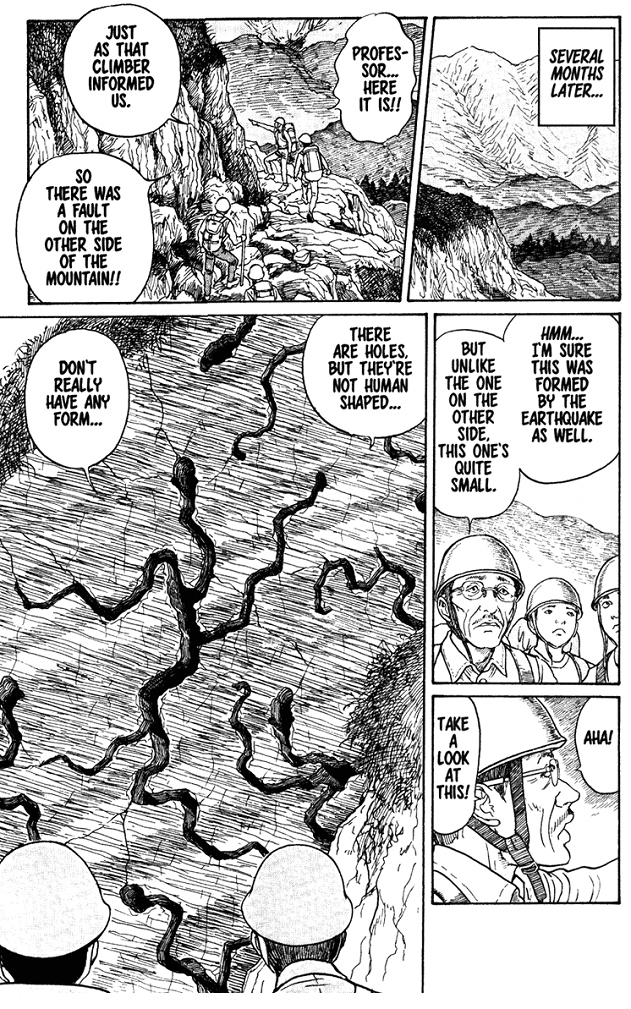

Even though I knew this was about swordsmen, I somehow didn’t expect it to be as gory as it is. There are a lot of death blows being dealt here, as Musashi is obsessed with measuring/proving his strength against others and willing to sacrifice his life to this aim. That said, at times the art is absolutely gorgeous, and there are a few color pages that look like bona fide paintings. The scope, layout, and pacing of the story all lend it a cinematic feel that is genuinely impressive. There’s one scene early on, when Musashi turns around to face the one opponent left standing and it’s genuinely terrifying.

But yet, I mostly found it unaffecting. I expect there will be more insight into the main character as time progresses, but for now he’s so closed off, so proud of his strength and being hailed a demon that I can’t grow fond of him or endorse his goals. I have a feeling I’m not supposed to. I did identify with Matahachi a lot, though, especially his inferiority complex in regards to his friend and his inability to follow through with the heroic deeds he imagines himself performing. I like Otsu, the fiancée Matahachi left behind, and I’m intrigued by Takuan, the monk. I’ll keep reading for them, if nothing else.

One thing about Musashi reminds me a lot of Hisanobu Takahashi in Real. As a child, Hisanobu was attempting to master a particular basketball move that his father showed him. He worked very hard on it, but was never able to show his father because the latter abandoned the family. Musashi has also been abandoned by his mother and shunned by his father, and part of his drive to test himself seems due to the desire to show them his strength, show them that he doesn’t need to depend on anyone else. Musashi is a real historical figure, not a character Inoue created, but it seems like he’s drawn to these confident yet wounded types.

Ultimately, I can see why Vagabond is hailed as a masterpiece, and I will certainly keep reading it, but my heart will always belong to Inoue’s sports manga, Slam Dunk in particular. The heart wants what the heart wants!

Vagabond is published in English by VIZ Media. Single volumes up through 33 have been published, as well as ten “VIZBIG” editions comprised of three volumes each. An eleventh VIZBIG edition is scheduled to be released in December. Inoue has recently resumed the series in Japan, so the upcoming release of volume 34 (October) will be the first new Vagabond released in English in two years.

Recent Comments