MICHELLE: It’s been a while, but Let’s Get Visual has awoken from its hibernation in time to celebrate the Takehiko Inoue Manga Moveable Feast. Joining me for this occasion is special guest host Anna Neatrour, who is also co-hosting the MMF with me! Welcome, Anna!

ANNA: Thank you! I am excited to join in on a Let’s Get Visual post for Takehiko Inoue, because I think he is one of the top contemporary manga artists. He has an incredibly detailed and realistic style that really sets his manga apart from other series.

MICHELLE: I just started reading Vagabond the other day, and there was one close-up picture of Takezo drawn with extreme care and obvious skill, and I thought, “Y’know, this should be the image that all manga fans carry around to immediately dispel the misconceived notion that all manga looks alike and/or involves big, sparkly eyes.”

ANNA: I think that Inoue’s style (particularly in Real and Vagabond) is probably more reader-friendly to Western comics fans who haven’t read much manga before.

MICHELLE: Yeah, probably so. I’ve often thought that Western comic fans would probably like a bunch of seinen manga if they’d give it a chance.

Anyways, I suppose we should proceed to get visual! The images I’ve chosen are the very first pages in the very first volume of Real.

I chose these images because they demonstrate how well Inoue is able to communicate Togawa’s character here without needing any words at all. Okay, sure, this guy is in a wheelchair, but he’s clearly driven. He’s pushing himself, possibly to the point of pain (if that’s what that one black panel represents). He has bulging muscles, so he’s clearly been at this a while. He’s moving fast. He may have a disability, but it doesn’t mean that he can’t take being an athlete seriously.

And then you turn the page and see that he is all alone. Inoue pulls back to show the entirety of the gym to emphasize Togawa’s solitude, and if that wasn’t enough, we get a glimpse of the empty school campus, as well. This sets the stage for what we later learn (which you mention in your review)—that Togawa’s attitude toward his wheelchair basketball team does not mesh well with his hobbyist teammates. Here’s a guy who is giving it his all, and he is the only one.

There’s just so much we can tell from this elegant introduction that it kind of blows me away.

ANNA: I agree that one of the things I like best about Inoue’s art is how much the images are able to contribute to the storytelling of his manga without overtly telling the audience anything. The themes touched on in the images you showed are addressed again later in the manga. Togawa’s ego and isolation contribute to his central struggle in the manga, and at the same time his willingness to practice all by himself shows just how dedicated he is to his sport.

MICHELLE: I will always, always be a big fan of nonverbal storytelling, so Inoue really wins my heart here by going above and beyond impressive art.

Want to tell us about the images you picked?

ANNA: The panels I chose were from Volume 26 of Vagabond, collected in the ninth VIZBIG edition of the series.

One of the reasons why I love Vagabond so much is that the fight scenes are never merely about two people fighting. There’s always a psychological or philosophical element involved. We see Miyamoto Musashi in a midst of battle against 70 members of the Yoshioka sword school, an ambush he willingly walked into. As he battles, he’s focused on centering himself and living in the moment. The close-up panels of his face show the process of self-reflection even as he is mowing down his opponents.

MICHELLE: That’s a really striking sequence. I like how he seems to be looking off into the horizon as he tells himself to have no aspirations for the future, as if to acknowledge the existence of other paths that he’s not allowing himself to take. Granted, I’ve not read the series that far—I’m barely on volume two—but it almost seems to me like he could walk away from this fight if he wanted to, but he’s not letting himself do it. Is that anywhere near the case?

ANNA: I don’t think Musashi is capable mentally of walking away from a fight like this. There are a lot of things that lead up to this sequence of many chapters where Musashi takes on the entire sword school, but one thing that struck me about the battle as a whole is that while you see Musashi getting beaten down and injured, towards the end Inoue almost has the reader concluding that it was really unfair to the 70 men who were planning on ambushing and attacking Musashi from behind that they had to go up against this one particular single opponent. Vagabond’s

fight scenes are always interesting, even when they stretch on for hundreds of pages, simply because the exquisitely rendered battles are contrasted with the internal struggles of the people who are fighting. Battle is as much of a mental exercise as it is a physical one.

MICHELLE: That’s an interesting point! So far I’ve only seen a few fights, and there hasn’t been much on Takezo’s (as Musashi is known at that point in the story) mental state yet. But I definitely admired the pacing and structure of Inoue’s artistic approach to battle—even watching Takezo just turn around and notice one opponent still standing becomes something frankly terrifying.

ANNA: One the things I enjoy about Vagabond is seeing the way Musashi changes over time. The man fighting the sword school in these panels has a measured sense of self and an inner stillness as he fights opponent after opponent. This is totally different from the way Takezo is portrayed in the earlier volumes, where he is more arrogant and animalistic.

MICHELLE: I definitely look forward to seeing how he gets from point A to point B. I admit, I still prefer Inoue’s sports-related series, but there’s just no denying that Vagabond is a masterpiece.

Thanks to everyone for reading, and we hope we’ve inspired you to check out some Inoue!

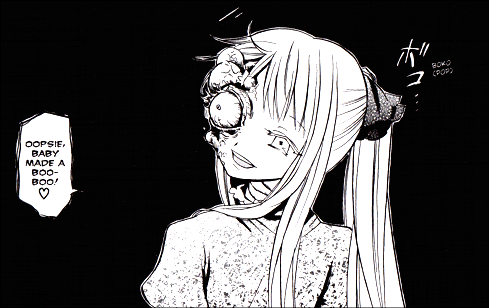

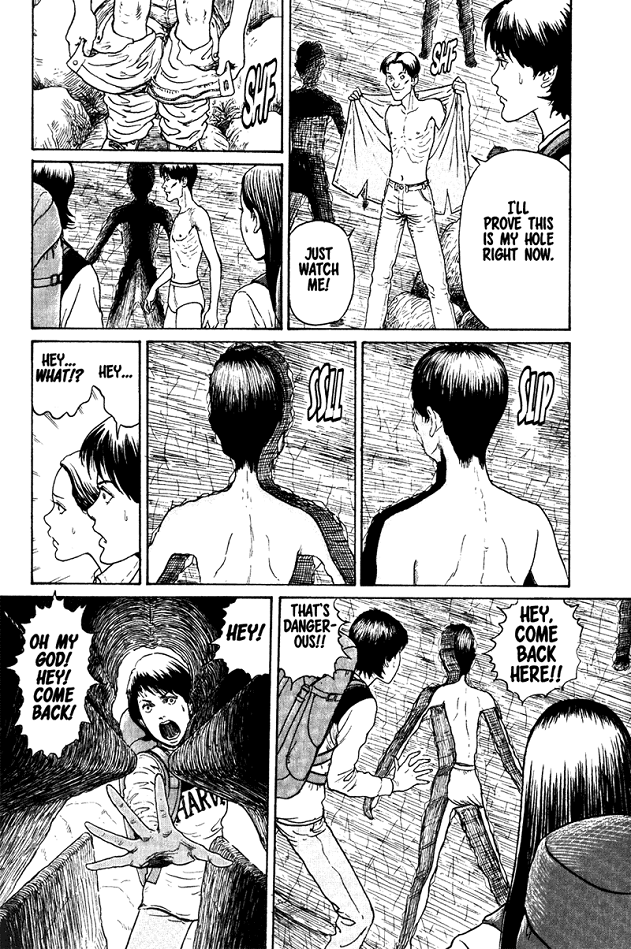

Fifteen kids—most of them, except for one boy’s kid sister, in 7th grade—are taking part in a summer program called “Seaside Friendship and Nature School.” Chafing at the instruction to go out and observe nature, the kids decide to explore a nearby cave, where they inexplicably discover a computer lab and a strange guy who calls himself Kokopelli.

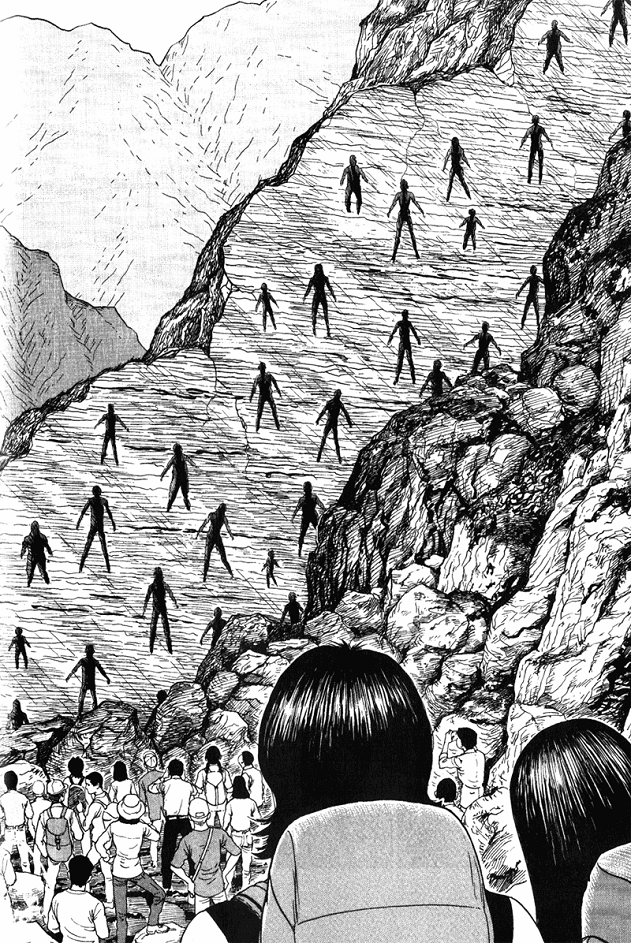

Fifteen kids—most of them, except for one boy’s kid sister, in 7th grade—are taking part in a summer program called “Seaside Friendship and Nature School.” Chafing at the instruction to go out and observe nature, the kids decide to explore a nearby cave, where they inexplicably discover a computer lab and a strange guy who calls himself Kokopelli. Bokurano is structured similarly, focusing on each pilot as he or she “gets the call.” There are merits and flaws to this approach: obviously, the current pilot receives a lot of attention, and it’s interesting to see how each approaches the responsibility differently. One boy cares nothing for human casualties while another carefully takes the battle out into the harbor to minimize damage. One girl uses her final hours to sew morale-boosting uniforms for the group. Unfortunately, this also means that at any given time there are about a dozen characters relegated to the background, waiting for their turn to contribute to the story.

Bokurano is structured similarly, focusing on each pilot as he or she “gets the call.” There are merits and flaws to this approach: obviously, the current pilot receives a lot of attention, and it’s interesting to see how each approaches the responsibility differently. One boy cares nothing for human casualties while another carefully takes the battle out into the harbor to minimize damage. One girl uses her final hours to sew morale-boosting uniforms for the group. Unfortunately, this also means that at any given time there are about a dozen characters relegated to the background, waiting for their turn to contribute to the story.

Recent Comments