By Naoko Takeuchi | Published by Kodansha Comics | Did I Mention Squee?

I think it’s probably impossible for me to be impartial about Sailor Moon. I just love it so much. The third season of the anime comprised one of my first exposures to shoujo anime, and even though I’m cognizant of its shortcomings, I can’t look back upon it and feel anything other than nostalgic adoration.

I think it’s probably impossible for me to be impartial about Sailor Moon. I just love it so much. The third season of the anime comprised one of my first exposures to shoujo anime, and even though I’m cognizant of its shortcomings, I can’t look back upon it and feel anything other than nostalgic adoration.

I’ve read the manga before. I was warned early on that the TOKYOPOP versions changed some characters’ names and relationships, so I never bothered trying to acquire them. Instead, I remember checking the website for Boston’s Sasuga Books (sadly no longer with us) regularly to see whether the latest volume of the gorgeous tenth anniversary edition was available for order. Reading each volume was a fairly painstaking process of matching a text-only translation to the images in the physical book. But one makes do.

Still, as with Codename: Sailor V, I feel like I got much more out of the experience this time when reading a professionally prepared English translation. It felt more immediate to me. Alas, though I would love to be able to report that Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon is free from the text errors that plagued Sailor V, I can’t. I only spotted four problems, though: two cases of misplaced sound effects (one only noticeable if you read kana) and two where the word “who’s” is used instead of “whose.” Pretty minor, yes, but still disappointing. I can’t be alone in wishing for a flawless edition.

Moving on!

Because Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon came about due to the earlier success of Codename: Sailor V, there are some obvious similarities in their lead characters. Like Minako Aino, fourteen-year-old Usagi Tsuniko is a below-average and perpetually tardy middle-school student with a fondness for video games. Where Minako craves the spotlight and is somewhat more bold, however, Usagi is a crybaby who’s inclined to take the easy way out. Both are informed of their special destiny by a talking cat—white (male) Artemis for Minako (Sailor Venus) and black (female) Luna for Usagi (Sailor Moon)—and both soon find themselves squaring off against “the enemy” whose plans invariably involve sucking energy out of the populace.

From the start, Usagi handles her duties differently than Minako. She’s more empathetic, but has a tendency to feel overwhelmed and require encouragement. (These are still, of course, early days.) She’s bolstered by her fellow guardians, however, and quickly accumulates three allies: the brilliant Ami Mizuno, guardian of water and wisdom (Sailor Mercury); classy and clairvoyant Rei Hino, guardian of fire and passion (Sailor Mars); and tomboyish yet girlish Makoto Kino, guardian of thunder and courage (Sailor Jupiter). Luna provides them all with information—I enjoy any scene that depicts the kitty in research mode—and handy gizmos that allow them to communicate and transform.

Together they face off against Queen Beryl and her Four Kings of Heaven, who are busily concocting schemes to collect energy to revive their “great ruler” while simultaneously searching for the “legendary silver crystal.” (We learn more about the enemies here than in Sailor V, incidentally, which makes them much more interesting. It’s still slightly disconcerting to see how quickly some of them are defeated, though, considering how long they stick around in the anime. Nephrite, for example, is vanquished after just one chapter!) The Guardians want to find the all-powerful crystal too, and are also searching for “the princess,” whom they are duty-bound to protect.

Also searching for the “legendary silver crystal” is a handsome fellow called Tuxedo Mask, two words that efficiently describe his costume. He has dreams wherein a faceless woman begs him to find the crystal, and so he tries to comply. Usually his efforts consist of lurking around when Sailor Moon is busy confronting the enemy, so as to be ready to bolster her confidence. Meanwhile, in his civilian guise of high school student Mamoru Chiba, he and Usagi keep running into each other and exchanging insults. I never much cared about their relationship in the anime, but it actually kind of works for me here. Maybe manga!Mamoru is appreciably more dreamy than his anime counterpart, because I can at least see why Usagi finds him so appealing. In this volume, there’s also some question as to whether he’s friend or foe, which gives Usagi something to worry about. (In general, while I don’t mind hyper Usagi, I like her much more when she’s being serious.)

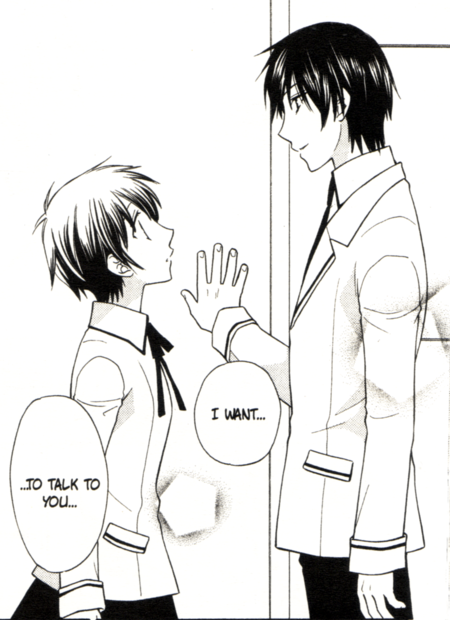

I would probably still like Sailor Moon if it were merely the story of a band of cute girls in colorful outfits who defeat the enemy with various nifty/goofy attacks like “moon tiara boomerang” and “flower hurricane,” but its feminist message definitely elevates it in my esteem. While Usagi may be drawn to Mamoru and while Makoto may yet pine for the sempai who rejected her, these girls are fully cognizant that they’ve got a mission that’s more important than romance. Consider this exchange in which Makoto is explaining her reason for transferring schools:

Makoto: It seemed there was something far more important… even more important than falling in love… that was waiting for me here.

Rei: You’re right! We don’t have the luxury of the time it takes to cry over a man.

Though normal teens until just recently, these girls are quickly coming to grips with their destiny and the enormous importance of preventing the crystal from falling into the wrong hands. One gets the sense that this experience, though dangerous, is going to be critical in forming who they become as people, especially lazy Usagi, who is now thrust into a leadership role. And even though Mamoru does help her on occasion, it never comes off as condescending, but more like he’s reminding her of the strength that she already possesses. He, after all, has no powers of his own so it’s up to her to save the day.

Thank you, Kodansha Comics, for licensing this series and giving us a proper translation at last. I’m happy for myself and other existing fans, but I also can’t wait to see what Sailor Moon newbies make of the story.

Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon is published in English by Kodansha Comics. They’ve licensed the tenth anniversary edition, which condensed the eighteen-volume series into twelve volumes of the main narrative plus two volumes of short stories. It also has pretty new covers and some retouched art.

Review copy provided by the publisher.

Recent Comments