By Jun Hayase | Published by Futabasha | Available in English at JManga

Even if JManga didn’t offer anything else to interest me, I think I would still love them forever for introducing me to Ekiben Hitoritabi. (The ekiben in the title refers to the boxed meals sold at train stations throughout Japan, while hitoritabi means “a trip undertaken alone.”)

Even if JManga didn’t offer anything else to interest me, I think I would still love them forever for introducing me to Ekiben Hitoritabi. (The ekiben in the title refers to the boxed meals sold at train stations throughout Japan, while hitoritabi means “a trip undertaken alone.”)

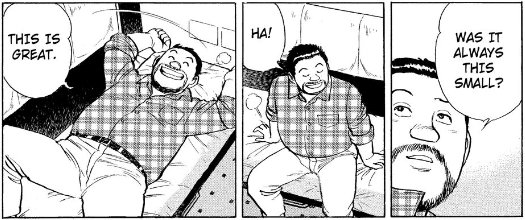

Ekiben Hitoritabi is a slice-of-life story about an ordinary 35-year-old train enthusiast named Daisuke Nakahara whose wife gives him a ticket to Kyushu by special express sleeper train for their tenth anniversary. Once he gets to Kyushu, Daisuke begins making his way north by taking a variety of local and little-used rail lines. He’s accompanied throughout most of the first volume by a journalist named Nana, whom he educates on railroad history and exposes to the wide variety of tasty ekiben to be found at the stations they visit. When they’re not rhapsodizing over the contents of these ekiben, they’re admiring the scenery or the trains themselves.

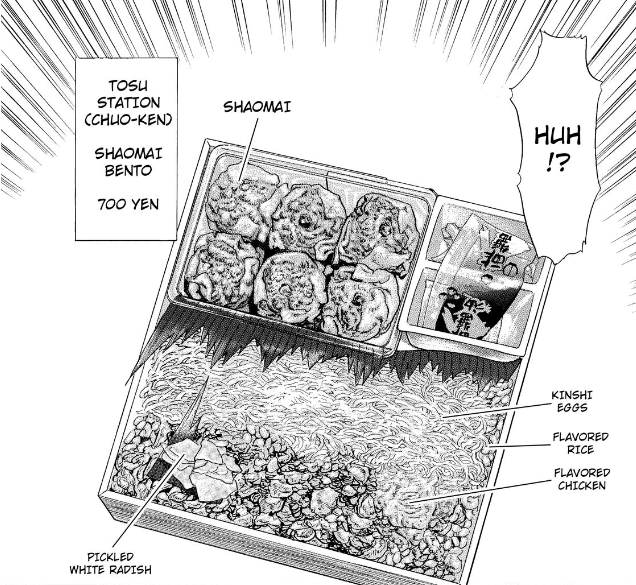

I don’t think this is a manga for everyone. The biggest source of tension, for example, is worrying whether Daisuke and Nana are going to miss their train when it’s taking longer than expected to procure ekiben. Daisuke likes everything he tastes—and, indeed, his love of ekiben has inspired him to open a bento shop of his own in Tokyo—and is in perpetually good spirits. There’s always a page turn before the contents of the bento are revealed, so that each always appears on the upper right-hand side, with each component identified. Someone is bound to make a remark about the taste permeating his/her mouth, too.

But it’s just so charming. (One learns a lot about Japanese geography, too.) Daisuke is content with his life and with taking his leisurely time, and he makes it look so awesome that I am frankly envious. Now I want to travel Japan by local rail and sample a bunch of ekiben! I must admit, though, that I’d be reluctant to try some of them. And the one that looked the best to me was the only one Daisuke had anything even slightly negative to say about. Here it is, the Shaomai Bento:

Shaomai is the Kyushu term for shumai, and after noticing that many of the ekiben contain kinshi eggs, I had to look them up and I WANT SOME ON RICE RIGHT NOW. That, of course, is the danger with Ekiben Hitoritabi: reading it while hungry is sheer torture.

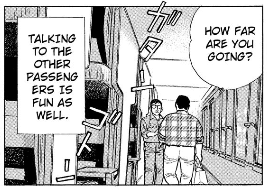

What’s not torture is the translation, which is better than I expected. I did get the sense that the work was spread between several people, however, because treatment of sound effects was inconsistent and some errors (like “bento’s” instead of “bentos”) cropped up only intermittently. I never had any issues with comprehension, though, and JManga welcomes feedback, so I did leave them a few notes about the minor problems I noticed. Splitting a word between two lines seemed to be an issue, for example:

On the whole, however, I am utterly delighted that I got to read Ekiben Hitoritabi. I doubt it would’ve sold too well in print format, so if digital is the only way I can get it, then I am just grateful to have the chance. Grateful and yet impatient, because I am going to need volume two pretty soon. And some kinshi eggs.

Ekiben Hitoritabi is up to volume thirteen in Japan and is still ongoing.

Recent Comments