By Rize Shinba (manga) and Pentabu (story) | Published by Yen Press

The good news is that I liked My Girlfriend’s a Geek more than I expected to. The bad news is that I’m not sure if I should feel particularly good about that.

The good news is that I liked My Girlfriend’s a Geek more than I expected to. The bad news is that I’m not sure if I should feel particularly good about that.

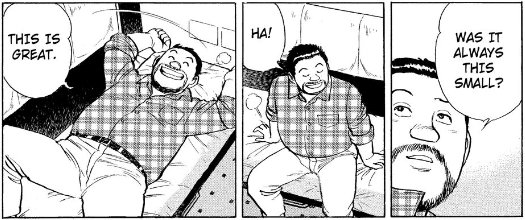

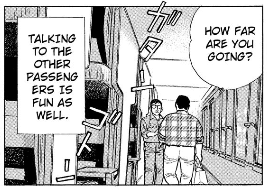

Taiga Mutou is a penniless college student in need of a part-time job. When he spots Yuiko Ameya—who fits his ideal of the “big sis-type”—in the office of one prospective employer, he devotes himself to getting hired and thereafter attempts to find opportunities to engage her in conversation. He’s largely unsuccessful until a bit of merchandise goes missing and she helps him look for it. They talk a bit more after that, but it’s not until she sees him in a pair of glasses that she really begins to take notice.

At first, Taiga is puzzled but pleased that certain things about him meet with Yuiko’s approval—in addition to the glasses she also appreciates his cowlick and has an unusual level of interest in his methods for marking important passages in his textbooks. When he finally asks her out and she confesses that she’s a fujoshi (“Is that okay with you?”) he’s so exuberant that he agrees without really understanding what that entails.

From that point on, My Girlfriend’s a Geek is essentially a series of situations in which Yuiko’s fujoshi ways make Taiga uncomfortable, and here is where my conflicted feelings begin. On the one hand, it’s absolutely true that Yuiko did try to warn him and that she shouldn’t have to pretend to be someone she isn’t. On the other hand, she is so caught up in her BL fantasizing that she never considers Taiga’s feelings, and even ceases to refer to him by his actual name. Taiga is always the one doing the compromising, and when it seems like Yuiko might be on the verge of doing something nice for him, it usually turns out that she has some self-serving motive.

From that point on, My Girlfriend’s a Geek is essentially a series of situations in which Yuiko’s fujoshi ways make Taiga uncomfortable, and here is where my conflicted feelings begin. On the one hand, it’s absolutely true that Yuiko did try to warn him and that she shouldn’t have to pretend to be someone she isn’t. On the other hand, she is so caught up in her BL fantasizing that she never considers Taiga’s feelings, and even ceases to refer to him by his actual name. Taiga is always the one doing the compromising, and when it seems like Yuiko might be on the verge of doing something nice for him, it usually turns out that she has some self-serving motive.

And what if Yuiko’s character was male? How would this read then? She frequently concocts scenarios in which Taiga is getting it on with his friend Kouji and expresses the desire to take pictures of them together. If she was a male character saying such things to his girlfriend this would be the epitome of skeavy behavior! I seriously wonder whether she likes Taiga for himself at all, but that’s not to say he’s blameless here, either, because it’s hard to see what he could like about her except that she fits the bill for the cute older woman he’s always wanted to date.

All that said, there is still quite a bit to like about this series. For one thing, it’s often quite amusing, especially Taiga’s reactions to Yuiko’s flights of fangirl and the fictional shounen sports manga (with shades of Hikaru no Go and The Prince of Tennis) that Yuiko is obsessed with. For another, it does occasionally touch on what it’s like to discover that someone you fancy has this bizarre secret that you’ve got to try to cope with if you want to stay together. Taiga occasionally laments how far apart they are emotionally, and though we’ve yet to really see inside Yuiko’s head, her attempts to sustain a real-life relationship remind me some of Majima in Flower of Life, another hard-core otaku with a moe fixation.

All that said, there is still quite a bit to like about this series. For one thing, it’s often quite amusing, especially Taiga’s reactions to Yuiko’s flights of fangirl and the fictional shounen sports manga (with shades of Hikaru no Go and The Prince of Tennis) that Yuiko is obsessed with. For another, it does occasionally touch on what it’s like to discover that someone you fancy has this bizarre secret that you’ve got to try to cope with if you want to stay together. Taiga occasionally laments how far apart they are emotionally, and though we’ve yet to really see inside Yuiko’s head, her attempts to sustain a real-life relationship remind me some of Majima in Flower of Life, another hard-core otaku with a moe fixation.

There’s only two more volumes of this series and I plan to keep reading, but I hope that these characters will manage to achieve more of an equal relationship. Even if Yuiko could just learn to see Taiga’s exasperation and take some genuine step to engage him on a serious personal level, then I’d be happy.

My Girlfriend’s a Geek is published in English by Yen Press. The fourth volume has just come out (to be featured in this week’s Off the Shelf!) and the fifth and final volume is due in December 2011. They have also released the two-volume novel series upon which the manga is based.

Review copies provided by the publisher.

Recent Comments