By Junji Ito | Published by VIZ Media

As with Ito’s two-volume work, Gyo, the best word to describe Uzumaki—despite a back cover blurb promising “terror in the tradition of The Ring”—is “weird.”

As with Ito’s two-volume work, Gyo, the best word to describe Uzumaki—despite a back cover blurb promising “terror in the tradition of The Ring”—is “weird.”

High school student Kirie Goshima lives in Kurôzu-Cho, a small coastal town nestled between the sea and a line of hills. She narrates each chapter in an effort to share the strange things that happened there. It all begins when, on the way to meet her boyfriend Shuichi Saito at the train station, she spots his father crouching in an alley, staring intently at a snail. Shuichi confirms that his dad has indeed been acting odd lately, and suggests that the entire town is “contaminated with spirals.”

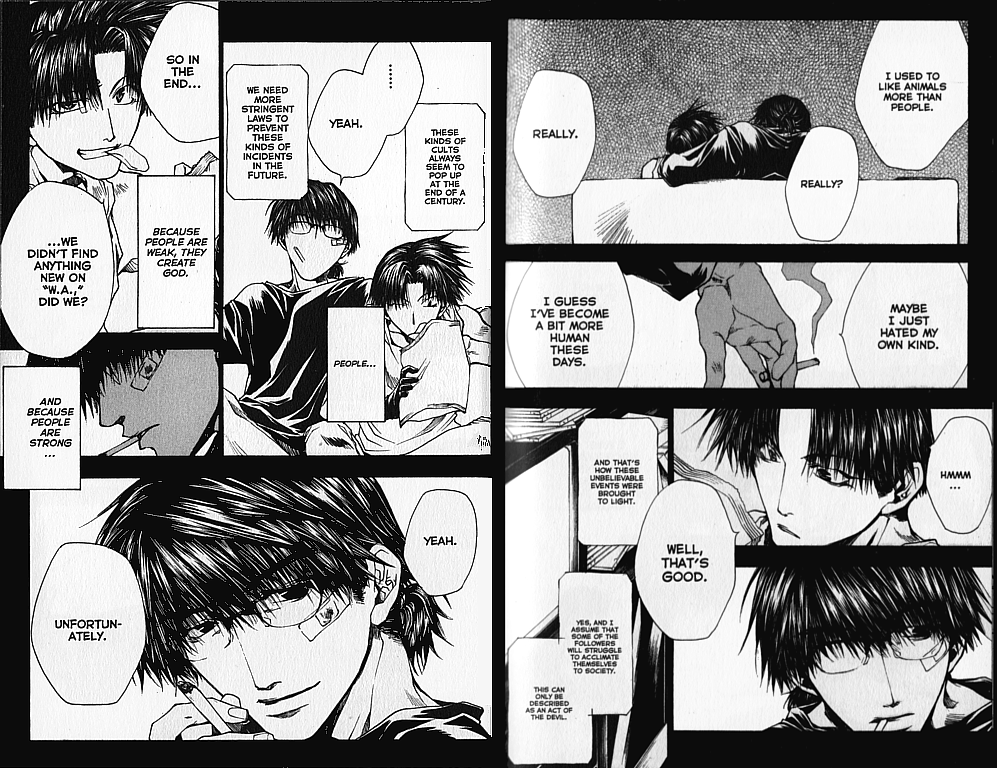

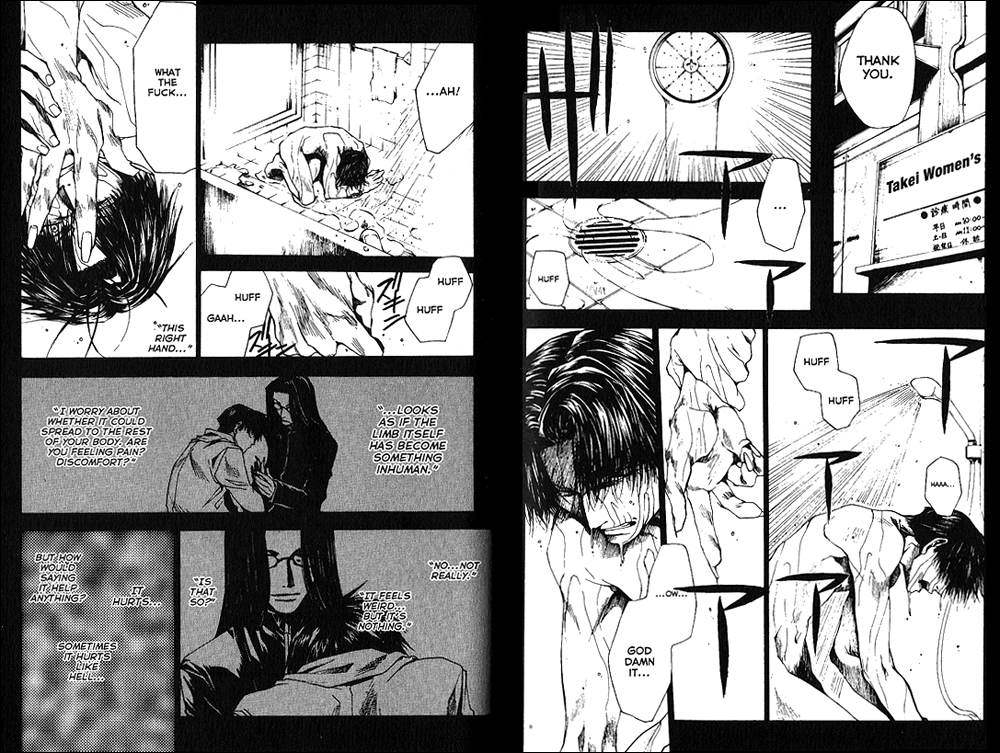

Mr. Saito’s fixation with spirals grows to the point where he dies in an attempt to achieve a spiral shape, which drives his wife insane with spiral phobia. She too eventually passes away, leaving Shuichi alone to become a recluse who is able to resist the spiral menace while being more perceptive to it than most. Other episodic incidents fill out the first two volumes, including unfortunate events involving Kirie’s classmates (boys who turn into snails, a bizarre rivalry over spiralling hair, etc.), her father’s decision to use clay from the local pond in his ceramics, a mosquito epidemic that leads to icky goings-on at a hospital, and an abandoned lighthouse that suddenly begins producing a mesmerizing glow. Things come to a head in volume three when six successive hurricanes are drawn to Kurôzu-Cho, leaving it in ruins. Rescue workers and volunteers flock to the area, but find themselves unable to leave. Dun dun dun!

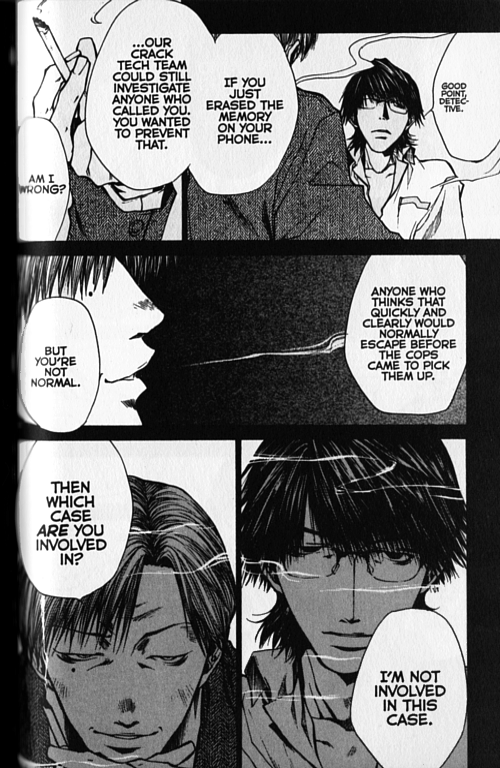

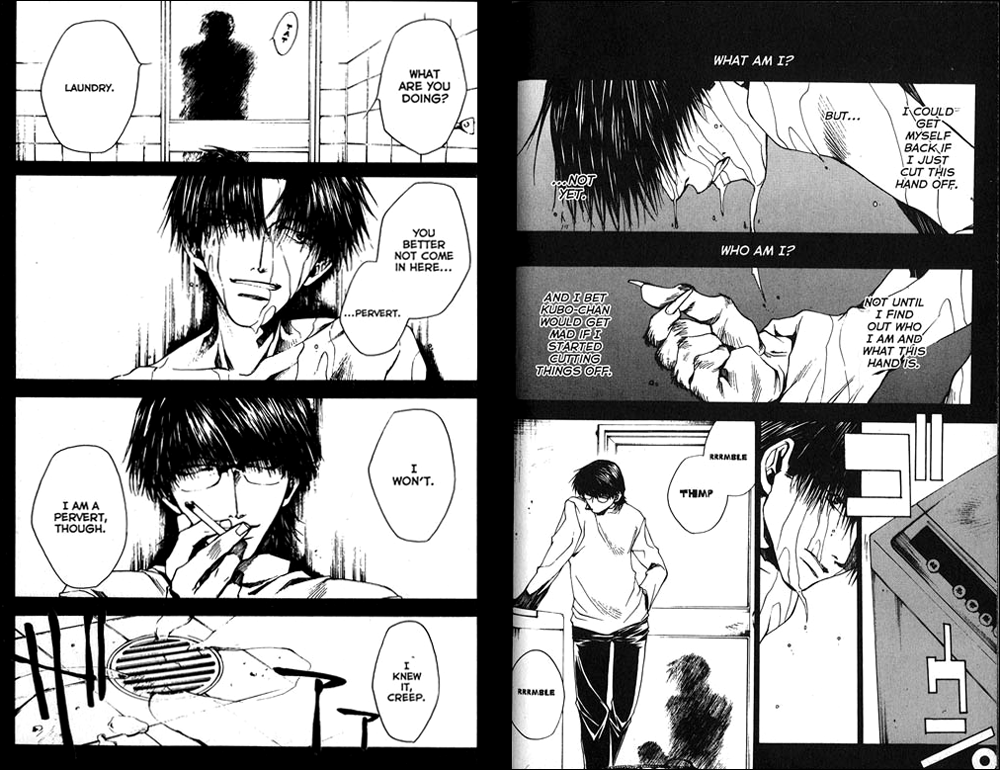

Creepy occurrences mandate creepy visuals, but I wouldn’t say that anything depicted herein is actually scary. Oh, there are loads of indelible images that made me go “ew” or “gross,” but was I frightened by them? No. The real horrors of Uzumaki are more subtle: the suggestions that there are ancient and mysterious forces against which humans are utterly powerless and that the spiral’s victims will live in eternal torment. Many tales of horror involve bloodthirsty monsters, but a menace that forces you to live and endure something horrific is much more capable of giving me the jibblies. It’s the ideas behind Uzumaki, therefore, and not the surfeit of disturbing images, that evoke dread.

Creepy occurrences mandate creepy visuals, but I wouldn’t say that anything depicted herein is actually scary. Oh, there are loads of indelible images that made me go “ew” or “gross,” but was I frightened by them? No. The real horrors of Uzumaki are more subtle: the suggestions that there are ancient and mysterious forces against which humans are utterly powerless and that the spiral’s victims will live in eternal torment. Many tales of horror involve bloodthirsty monsters, but a menace that forces you to live and endure something horrific is much more capable of giving me the jibblies. It’s the ideas behind Uzumaki, therefore, and not the surfeit of disturbing images, that evoke dread.

Uzumaki has a much larger cast than Gyo, which prompted me to notice that Ito actually draws some really cute and realistic-looking female characters. Kirie is a prime example, but her classmates and TV reporter Chie Maruyama also fit the bill. I was pretty distracted by Ito’s rendering of a girl named Azami, though, because she reminded me so much of Madeline Kahn as Mrs. White in Clue. Observe:

Uzumaki definitely delivers an unforgettable story with memorable art, but I would’ve liked to get to know the characters more. Kirie is a reasonably accessible lead and is smart, strong, and kind, but I felt at times that she was too strong. If anything gross is going on in town, Kirie is the one who’s going to discover it, and though she reacts in the moment, there wasn’t much emphasis on the cumulative effect of having witnessed all this madness. She keeps going and being shocked by things right until the very end, but a more normal person would’ve broken down long before. And why weren’t more people fleeing, I wonder? True, once the storms hit, nobody could leave, but for a while there plenty of crazy stuff is happening and folks are just sticking around.

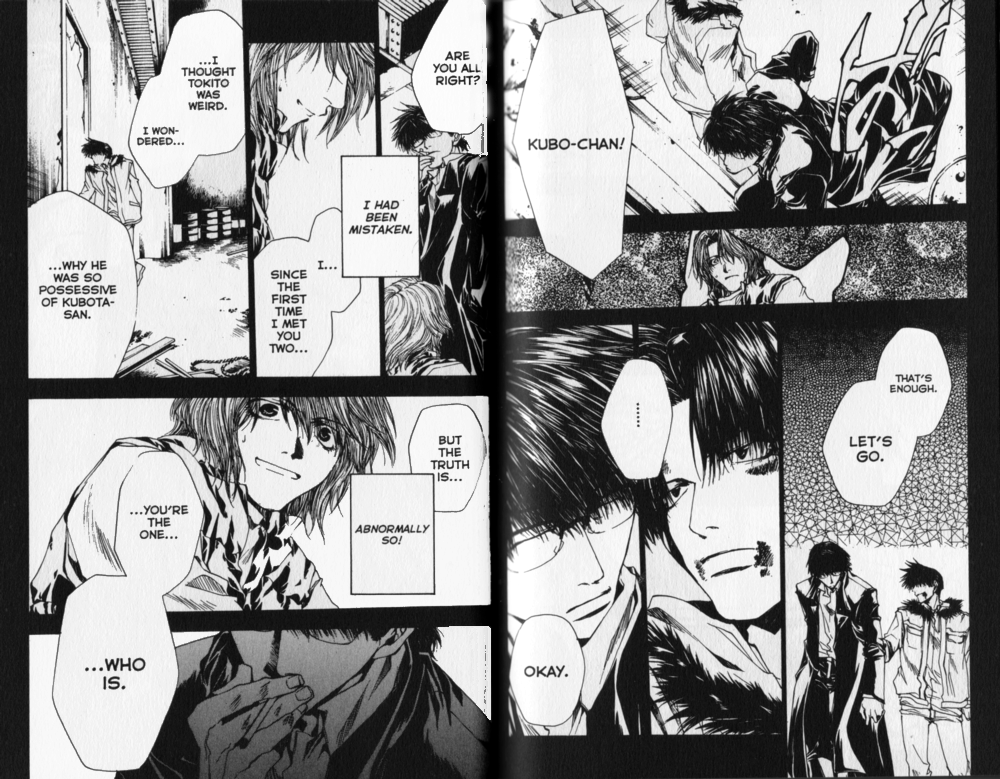

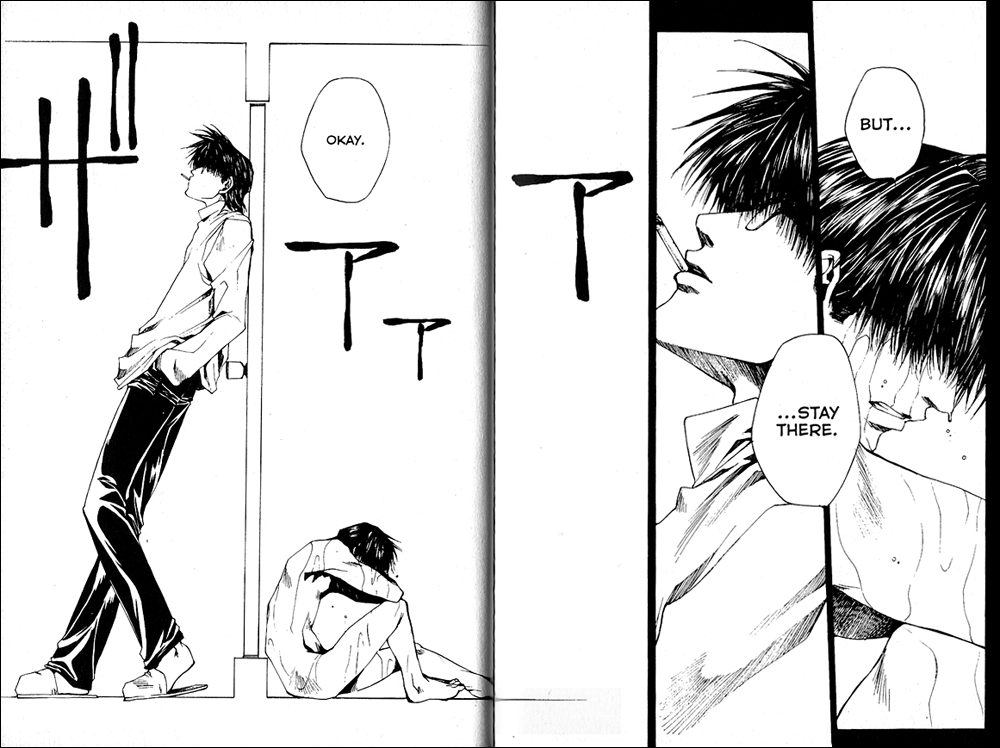

I also would’ve liked to spend more time with Shuichi. He’s a pretty interesting guy, who wants to get out of town from the very start but remains because of Kirie. He seems to have inherited equal parts fascination with and fear of the spiral from his parents, which keeps him alive if not entirely sane, and is able to function at times when others are mesmerized, allowing him to come to Kirie’s aid on several occasions. Through these actions we see how much he cares for her, but I actually had no idea they were supposed to be a couple until he was specifically referred to as her boyfriend a couple of chapters in. Okay, yes, this isn’t a romance manga and I shouldn’t expect a lot of focus on their relationship, but even just a little bit of physical affection would’ve gone a long way.

I also would’ve liked to spend more time with Shuichi. He’s a pretty interesting guy, who wants to get out of town from the very start but remains because of Kirie. He seems to have inherited equal parts fascination with and fear of the spiral from his parents, which keeps him alive if not entirely sane, and is able to function at times when others are mesmerized, allowing him to come to Kirie’s aid on several occasions. Through these actions we see how much he cares for her, but I actually had no idea they were supposed to be a couple until he was specifically referred to as her boyfriend a couple of chapters in. Okay, yes, this isn’t a romance manga and I shouldn’t expect a lot of focus on their relationship, but even just a little bit of physical affection would’ve gone a long way.

Uzumaki is grim, gruesome, and a whole host of synonyms besides. This isn’t jump-out-of-your-skin horror, but a psychological tale with a decidedly grisly bent. I’m not sure I’d universally recommend it—I think I know several people who definitely shouldn’t read it, actually—but if it sounds intriguing to you, give it a whirl.

Uzumaki was published in English by VIZ Media. It is complete in three volumes.

For more entries in this month’s horror-themed MMF, check out the archive at Manga Xanadu.

Recent Comments